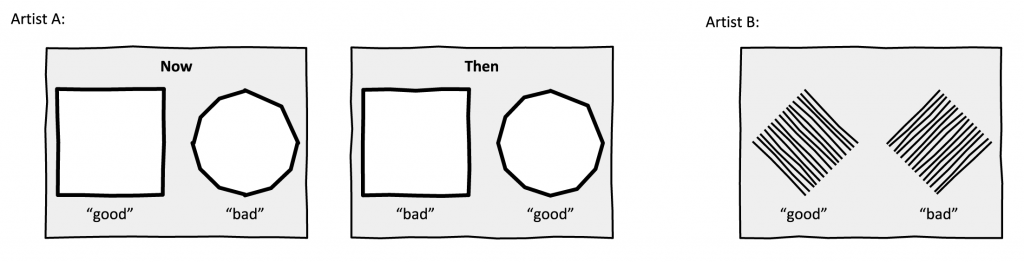

As an artist, your highest goal is to understand your own ideas of quality, to grow with and expand them. Your standards will keep changing, just as you do, and sometimes conflict with each other: some works will need to scream, while others will need to be silent. Some works will need to do both. Think of your quality criteria as a rhizome, something of depth and complexity, and endless connection points: like a symphony, or a plant with indefinite subterranean roots. Something that can incorporate varying ideas of strength and power without opposition or conflict: to be slow yet strong, dedicated yet open. Over time, you’ll understand overarching standards that encompass, include, and potentially replace your prior ones: where smoothness of movement might have been relevant initially, your focus might shift to full choreographies – and later return to the initial focus. Quality standards are ever-shifting, just as you are. They will morph along your moods and life phases, carrying the potential for endless surprises.

How to Find Quality in Your Work

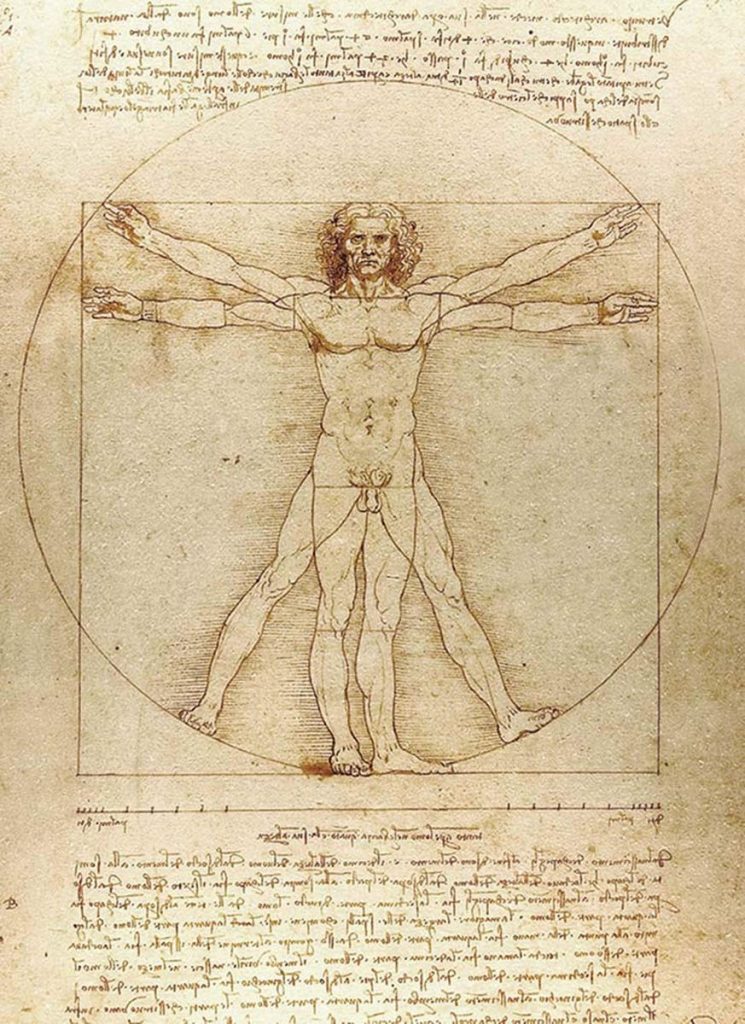

You establish your quality ideals by mindfully immersing yourself into art, and life. They are a consequence of all your aesthetic and semantic preferences, including all your affinities and actual capabilities. The more sensitive you are about understanding what matters to you (media, processes, tools, aesthetics and content), the more likely you’ll establish ideals that suit you. You’re never bound by current limitations though: your today’s capabilities can change tremendously, based on your willingness to invest time and effort.

Whenever you create something, you also form a value judgement: about what worked, and what didn’t. About what moved you, or moved you too much, or didn’t move you enough. About what was too bright, too large or too slow. About the little things that might require change to result in something to feel perfect: sounds, movements, traction; density and weight; haptics and fluidity, etc. The same is true when experiencing the world: what food, hobbies, politics or social agendas you care about. Quite obviously, your affinities are deeply personal – yet your choices can sidestep them: you might like something, but decide against it; your bias might exist on a general level, but not specifically when discussing the current artwork.

Art History

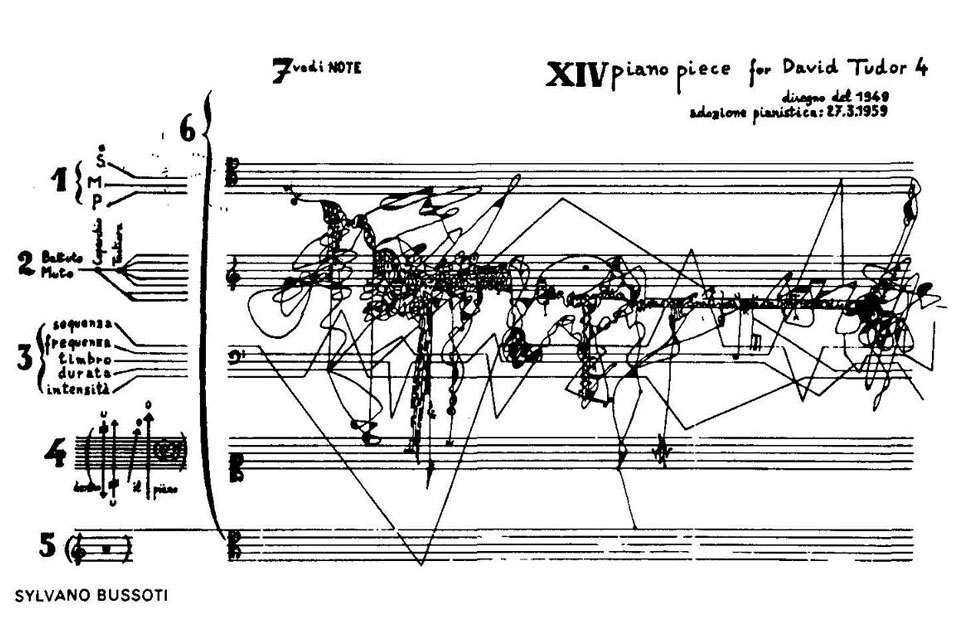

While your quality criteria are yours to establish, art has a tremendous history of choices. The more you know about them, the better you will be able to connect to someone else’s choices, and continue or transcend what’s been established before you. Doing so changes your art practice from the pursuit of pure personal expression, to the proactive advance of a medium’s history. While artworks always focus on something, this adds another focus point: art history. As such, it defines your way of interacting with art per se, putting it on the same level as worldly topics. Understand that your focus on art history can lead to art that unbalancedly cares about the past – any of your choices can have the (subconscious) intention to find a secure hiding spot, a place to rest. These rarely exist in the arts, which benefit from courageous approaches. The challenge is to find a way to incorporate your self-expression in a way that reflects the past, and potentially helps to bring it into the future. For this, your references don’t have to be obvious or explicit – they don’t even have to be understood. By existing in your mind, and during the creation process, the artwork usually creates a spin that sticks, an aura that’s hard to describe but there to be felt.

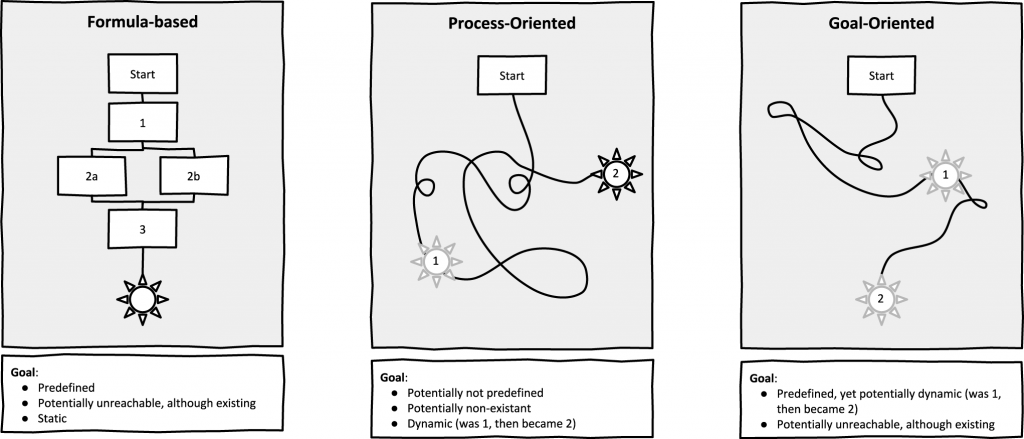

Hiking without a Compass

Consider hiking in unknown territories, without a compass to guide you. You might never reach your goal: every direction is equally feasible. You might want to rest and wait for help, but the endless horizons in each direction don’t promise anyone’s arrival anytime soon. Yet you could reach your goal by simply deciding on a direction, and by starting to walk. You might want to change directions after a while, potentially subverting your previous choices. You might notice life around your path as exciting yet worrying, and keep moving. While you’ve walked for a longer time already, you notice that there might never be a goal. You get frustrated, worried, fearful – until you realize that walking actually is the goal.

This is both worrying and liberating: instead of an external goal to get to, you understand to be embedded within one already. You don’t trust this insight too much though, and keep moving. Over the years, you realize that you can walk in all sorts of ways: slowly, gracefully, weirdly; you can crawl or walk backwards, you can even dance or whistle along the way. On really good days, you move according to your inner self, without any thoughts on how it might look like, or how incredibly stupid the whole act of walking might be. Your increasing awareness of the endless ways of moving let you understand that this pursuit of moving, of the various modes of walking, is what ultimately defines you.

The pursuit of a goal resulted in you walking, and turned to you thinking of maybe, just maybe, yourself as being the goal. Once you truly understand this, you set up camp. The sun sets. You build a home, and decorate it with experiences and schemes. You still go for hikes, but look forward to returning to your camp. You don’t explore the world as much as you used to. You found a home, by walking the earth.

Understand that the artistic process consists of the pursuit of .. itself. It’s a deeply self-reflecting, self-referential system, based on your own sensitivities and creations. This system is then used to process the parts of life that you care about. While you can attach yourself to the beliefs and ideals of others, this will remove your voice from the world – maybe even before it was ever formed. By fostering an atmosphere of benevolence towards experimentation, you can raise your own awareness and sensitivities: about what you want, and who you might be. Without these, you can imitate others, but won’t be able to develop your voice, your ideas, your interpretation of the world. You’d be silenced, and stripped of your power.

Read the previous chapter to understand what quality is, and why it is relevant for artists.