You start making art by embracing an exploratory mindset, which helps you to investigate the potential quality ideals of your work.

Starting something can be both magical and frightening: beginnings require us to transcend our fear of failure. They let our hopes for success meet the realities of our abilities, and of our willpower: sometimes doubts win, and we stop before ever having begun. Beginnings can be complex – you might not know what to do, how to go about it, or even why you’re getting started. Your actions might become a beginning, without you yet being aware of it.

Beginnings are a frequent challenge for artists, maybe more so than for others: entering a new project with unknown parameters, a collaboration with unclear outcomes. Kicking off a new medium, starting one’s first sculpture ever, or a new series after the previous one didn’t resonate with others. Apart from curiosity and a certain willfulness or giddiness, beginnings require hope – and the belief that we can be more than we are right now. They are quintessentially human.

Beginnings require hope, and the belief that we can be more than we are right now. They are quintessentially human.

The beginnings of artistic processes can be unexpectedly erratic, since they can’t rely on external quality ideals – processes can legitimately begin without knowing where they are meant to go. These quality ideals can exist upfront (as the result of previous artistic interrogations, or general personal semantic or aesthetic preferences), or have to be established while pursuing the process, resulting in them often being inherently experimental. The notion of artistic processes having to be experimental is so normative to some, that sometimes an artist’s authenticity is judged by it: if your art is visually similar to your previous work, or that of other artists, it might be seen as inauthentic (“You’re just copying yourself!” or “You’re just copying others, instead of pursuing your own vision! Art is only art if its processes are unstable!”). This can lead to artists feeling self-conscious once their processes become more established and stable – as if there’s only merit in the pursuit of unknowns. The actuality is that the art making process has different phases: some more experimental, some more production-oriented. Both are necessary.

Artistic processes often don’t have a clear sequence of steps to pursue; there might be knowledge about tools and materials, but little absolutes about how to reach the goal (which doesn’t need to be defined upfront). With neither processes nor goals being clearly defined, artistic processes often start radically erratic and open-minded, and can benefit from a certain naivety. How to ever get somewhere this way?

Exploratory Processes

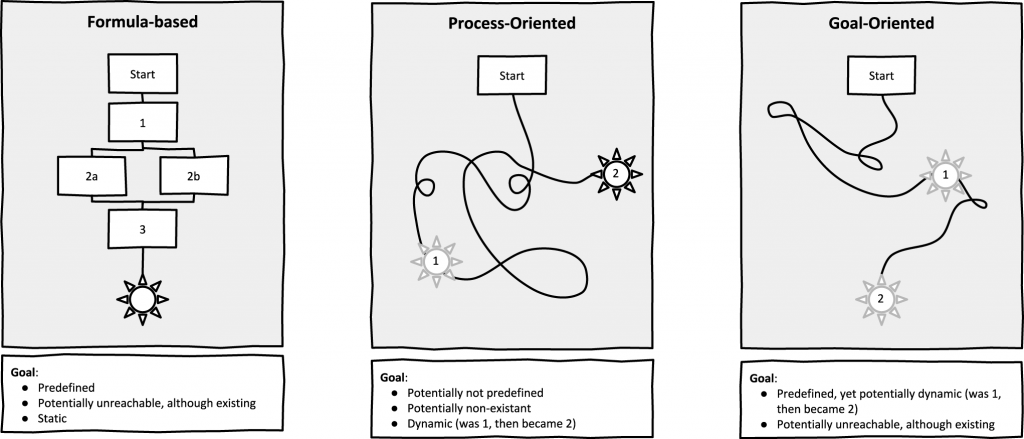

Many creative processes follow a predefined, sequential formula (“do this, then that, then that, ..”); they offer a sequence, and thus guideline, within which creativity (and thus personal choice) finds room. In the arts however, there often is neither sequence nor guideline – the processes can be more fundamentally open and exploratory: you can draw a figure or an abstraction on your piece of paper, or you can fold the paper, or rip it apart, or burn it and create work out of its ashes. You can draw a figure on paper, but focus on the pencil being used up (and not what you were drawing).

Exploratory artistic processes need to establish what they are about, and how they go about it. In the case of process-oriented artistic practices, this pursuit can even represent the goal, with a specific end condition being used instead of otherwise defined quality criteria: a certain time having passed, materials having being consumed, etc. These practices ultimately don’t need anything but the urge to start: one can doodle and experiment freely, to end whenever it feels right. For goal-oriented practices, the artist needs to develop some sort of understanding of where to get to, and how to get there. For production phases, one would usually want to know both these aspects; for exploratory phases, one ultimately needs neither: it suffices to get going, and stay sensitive towards one semantic and aesthetic ideas.

.

Finishing and Quality Criteria

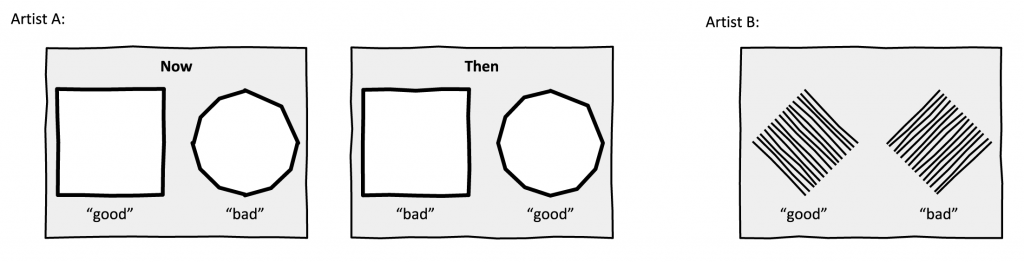

Finishing something requires you to understand and reach that thing’s finish line – which in arts is represented by your quality ideals: when does a painting, a sculpture, a novel, a dance fulfill the various criteria that you require of it? These quality criteria can be aesthetic (“A blue sun has been sculpted in a way that’s pleasing to me”) or conceptual (“Thirteen body movements have been made between 6:07 and 7:06pm”) – offering endless potential for confusion to laypeople. This is made even more volatile by quality ideals not only being highly personal, but also being subject to time: a specific variation of a sculpted blue sun might look beautifully complete to Artist A, but decidedly worthless to Artist B; these personal points of view do not stand in conflict with each other (although certain people will, antagonistically, lecture others about which quality criteria they feel to be “right”), since everyone is ultimately required to have their own ideas about what’s finished or good – it serves as the basis for contemporary arts’ endless multitude of quality ideals and works. In addition, an artist’s ideas about finishedness and perfection don’t have to be consistent over time, but can vary in extreme ways.

It’s possible to finish an artwork even if you don’t understand whether it’s done – you can simply decide that you’ll leave it where it stands. If you don’t understand your quality ideals, you cannot know whether your current work satisfies them; you need to start interrogating (this might be the case because you are new at making art, or because you are experienced, but enter a new medium or concept where your ideals don’t feel adequate). You do so by embedding yourself in the processes of creation: either by using the tools and materials (pencil, hammer, your tablet, etc.), or by conceptualizing your quality ideals theoretically (“I want bold lines and large canvases”, “I want fragility mixed with cheekiness”, etc.) – or both. You increase your sensitivity and your judgment.

Over time, this fills the initially empty pot of quality with purpose and intent. Your ideas about a work’s (potential and actual) quality ideals will emerge from being immersed: you understand them because you focus, and experiment with your decisions. Before this can happen though, one has to begin – potentially without yet being able to properly understand where to go. This isn’t nearly as bad as it sounds; it’s like hiking with the intention to explore, which requires you to stay attentive and calm, and to carry on. You start without compass or map – but by walking, you get a better understanding of the territory, and the many options you have. Your walking becomes compass and map. You aren’t an explorer because you reach a goal; you are an explorer because you explore. Art requires a lot of this – it enables you to understand the territory, and your place(s) within it. You will get to judge which views you enjoy better than others, which in turn will give you moments of joy. The more of them you have, the better your life will often feel. Yet having a view at all starts with your first step: the beginning.

While it’s impossible to finish a work with unclear quality criteria, it’s absolutely possible to start working on it. Quality is a vacuum, which can eventually be replaced with purpose and intent. Quality can emerge from exposure to, and being embedded in a process. Before this can happen though, one has to begin – potentially without yet being able to properly understand where to go. This isn’t a bad situation – it’s like hiking to get somewhere unknown: you can’t get there without starting off, even though you might not always know whether the direction makes sense. You start without a compass or map – but by walking, you get a better understanding of the territory, and where it all might lead to. Your walking becomes compass and map. You aren’t a hiker because you reach a goal; you are a hiker because you hike. Art requires a lot of wandering – the more you can set up processes whose views you enjoy, the better your life will be. Having a view at all starts with your first step: the beginning.

In an open field like art, it can be hard to understand why to choose any specific direction over another – all of them are possible, and often mean the same to a beginner. There’s just not a strong compass yet. To establish one, consider using the following 3-tier structure:

Consider reading the chapters for a detailed discussion of each of these topics.