The beginning of artmaking is often marked by a deep curiosity about tools: how does the stroke of a pencil lead to a line; how does the sharpened wood of a pencil smell; how do different textures of paper feel like. Artists need to understand how to use their tools and media, but also what these tools and media mean to them; specifically, this includes increasing their awareness and understanding of the oftentimes complex emotional, haptical and somatic connections they have towards them. Everyone has their own approach towards an artistic medium – no two people use a pencil the same way, see a sculpture exactly with the same focus, have the same emotions or associations towards eg. the texture of a specific kind of paper. Already on the level of material, our takes on the universe differ – which is why improving our sensitivities towards the unique relationships within them matter so much. There cannot be a general way of using tools or artistic media: understanding our individual approach towards them requires introspection; we need to deepen the relationship with ourselves.

From tools to craft

Our curiosity about tools usually leads to (or is accompanied by) a curiosity about craft: how to depict, how to abstract, how to use them towards the goals we desire. Craft is an essence of artmaking, and is entirely personal – it’s your knowledge of the tools you use, and your relationship towards them. Craft is infinite: you cannot “finish” studying these relationships. In addition, craft offers the fantasy of comparison; the false hope that you could compare your abilities to those of others. If it were true, you might be able to become “better” than someone else. These sorts of comparisons are inherent to capitalism, and often seen as a motivational force. Artists can fall into this trap just like anyone else: “If I were better, or the best, then by merely focusing on craft, my work might become visible, and, who knows, collected and accepted”.

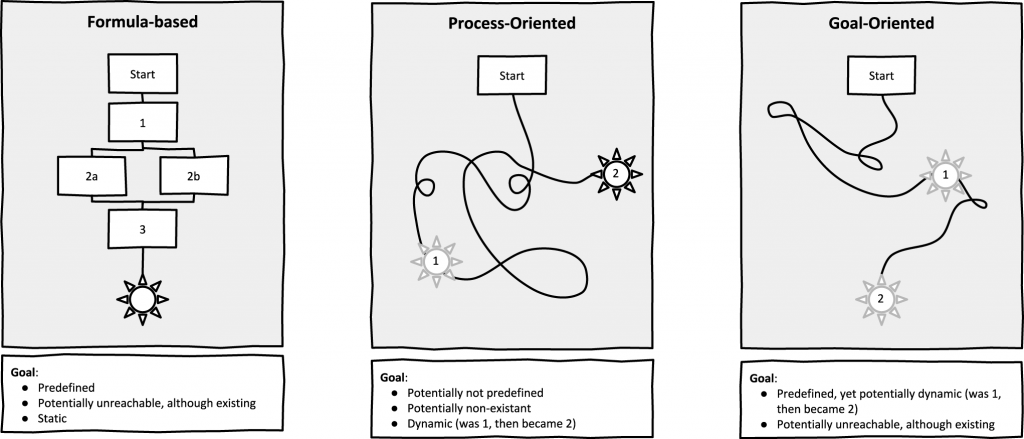

Art as transgenerational dialog that benefits from diversity

It doesn’t work like that though, since art isn’t a competition – but a transgenerational dialog benefiting from diversity: your voice is relevant only because of the other voices in the field – past, present and future. Voices and identities and cultures and realities you will never know or comprehend. There’s no goal to reach, but a process to pursue; ultimately, this process can become your goal: not to quit. To keep making art. Whatever increases the chances of your continued artmaking, is good – or even essential. If your focus on craft empowers you, then it’s worthwhile. At the same time, understand (the risky psychological benefits of) craft as a hiding place: you can keep increasing your focus on it, but still never reach the “true territory” of artmaking – because while art has craft as an essential base, it can only ever be a starting point for what art actually is about: meaning.

From craft stagnation to your passions, and your mind

So you focus on craft, because it helps you to focus on artmaking. You keep improving, and experience both progress and stagnation – both being inherent aspects of growth. You will establish plateaus of knowledge where further progress might feel distant. If this leads to your work feeling stale or boring, and you experience yourself repeating the same motions, then it might be a good time to sidestep craft, and consider what to actually do with it – with this deep emotional, haptical and somatic knowledge you established.

You are human before you’re an artist.

You are human before you’re an artist; and as a fellow human with passions, curiosities, joys and fears, there’s something that moves you beside your focus on art and on craft. That “something” is what life is about – and what art is about. While craft can help you transform your vision into reality, it can in itself feel hollow. Knowledge and application of craft often need meaning beside themselves, to transcend emptiness. This is reinforced by contemporary art empowering any mode or depth of craft – the crudest aesthetics are finally understood to be just as relevant as the most refined and elegant: you don’t necessarily ever need to increase craft, to focus on meaning. While craft is essential, it’s also a lie. The only actual craft that artists need, is meta – and about attitude: to increase their understanding of what they want to do. To transcend doubt. To create. Seen this way, the only tool required to artmaking is the artist’s mind.

Art and meaning

Understanding potential domains of your artmaking practice is mostly a mental activity. Interrogating what’s meaningful to you could lead to focusing on your emotions about tools and the media you use (at times, your focus on craft can feel to be the only thing that matters to you), or on specific aspects of your artistic practice. It might also focus on the aspects of life that you care about – which will usually be entirely independent of your art practice. These topics that you care about, and your individual, specific way of caring about them, are as unique as the way you hold your brush, as unique as you see and experience the world. Connecting your artistic practice, your craft, with the topics you care about is one of the most gratifying, personal, and courageous things that artists can do. It’s the difference between reading books and learning to speak, to the courage of phrasing a sentence that speaks your mind. It lets your voice become real. It creates your artistic identity.

To interrogate meaning, you can put your haptic, craft-based tools aside. Instead of creating the next craft-based work, try to see craft (also) as a potential medium of avoidance – an avoidance of vulnerability. While there is vulnerability involved in learning craft (“It’s so embarrassing how I can’t get this thing right”), it is usually way easier on you than creating work that pursues (and physically manifests) your actual passions. To interrogate meaning, consider doing the following:

- Interrogate your passions: create a list of topics you’re passionate about. Then

- Consider which of these topics you want (or need) to connect to artistically. Then

- Think about how to do so: in regards to colors, forms, and potentially also in regards to your previous artworks.

Each of these steps can take days, or could be done within a couple of minutes. The duration of your focus isn’t important – what’s relevant is that you keep returning to this process of interrogation. It’s a process that will accompany you throughout your entire life. It will set you on a path of discovery that will at times be far outside of your comfort zone. It will be scary – but will also offer rewards beyond expectations.

A thought about art and nihilism

Some experience contemporary art as a field without values – as nihilistic. This often is the consequence of contemporary art offering such an unusual openness in regards to the use of materials and media, and the breadth of topics. While some experience this as true freedom, others only see a wasteland that feels hollow and meaningless: can there be meaning, if anything is possible? Of course there can be – meaning isn’t limited, and contemporary art reflects that; artists can use any mode of operation to express their topics.

Yet the more open a field, the more courage can be required to do something specific – and art benefits from being specific, even if the specificity focuses on randomness (to create a truly random work requires highly dedicated specificity). As a field with entirely open values, art is inherently the opposite of nihilistic – something with values cannot be nihilistic.

Understanding your creations (1/2): Create one artwork

The creation of physical works is the phase that follows conceptualization, at least if artmaking would be a linear process – it often isn’t. In such an idealized linear process, the next step would be to actually create work that tries to fulfill the criteria set above. Creating artworks is stereotypically understood to be the core aspect of artmaking. Symbolically speaking, it’s where you begin to exist (as an artist). In actuality, it’s difficult to understand the thresholds of artmaking – conceptualizing an artwork surely also fulfills the criteria of artmaking, even if the processes might only have happened in your mind.

It’s essential to eventually manifest your ideas physically, because it enables you to understand the actuality of your creations, which will often be far from the elegant fantasies you might have had about them. A creation can only be one thing; it is the opposite of infinity. It is the consequence of a multitude of decisions, conscious and subconscious, which accumulated in the creation of this specific artwork. While interpretations of this artwork might be infinite, the specific artwork itself is finite and specifically as it is. This can be a challenge for your ego. It can be humbling: “Out of all potentials, this is what I ended up creating?” It can help to see art as a process of approximation: to ever get closer, throughout your life, to manifesting your vision. This lets each of your creations exist as something “more” than merely being a result: it lets it mark the continuation of your artistic journey – a process that will last as long as you live.

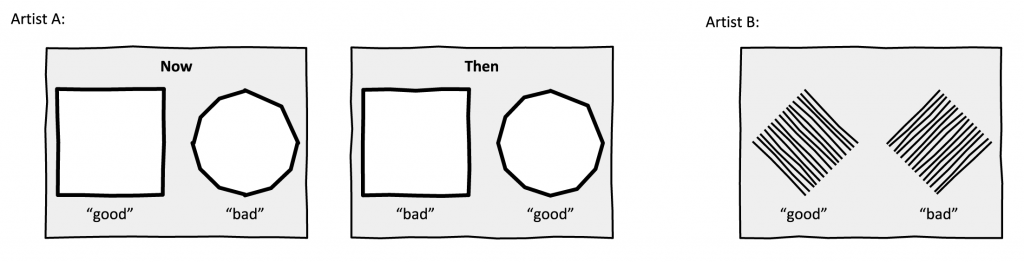

Understanding your creations (2/2): Create more than one artwork

Having created work enables interrogation and analysis. It enables you to ask questions like “How do you feel about it now? How do aesthetics and semantics connect?” To better understand what you think and feel about a piece, consider creating more than just one work, under the same criteria. Where a single piece will be the consequence of random choices, a multitude of works empowers you in judging this “style” – with style now denoting a mixture of aesthetics and semantics. Understand that this sequence of work doesn’t have to be a “work series”: where a work series often refers to visual repetition, a sequence of works is more open-minded, and includes works that might focus on a specific topic (eg. political paintings). Each of these might exist as a separate visual universe, and focus on a different political topic. To create a work sequence, consider doing the following:

- Interrogate the work you want to expand on: how is it defined? What are its essential qualities? It could be the specific use of tools, the physical format, the duration of a piece, the number of protagonists or movements within a performance, the choice and/or saturation of color, a modulation in frequency, the amount of figures or abstractions within a composition. It will likely also include semantic aspects like the chosen topic(s), and how to try to get them across. The essential quality could be entirely semantic, and not care about aesthetics, or it could include details whether eg. depicted figures have their eyes closed, look at (or away from) each other, etc.

This interrogation can be speculative – you might not yet understand what is essential to defining the work in front of you. Understand this process as another craft to improve over your lifetime, and keep returning to it. It will help you to gradually discover new aspects of your creations. - Create a list of essential qualities: Using the findings of your previous interrogation, create a list of those work qualities that feel the most relevant to you right now. It can be beneficial to limit yourself to 5-10 of these, and create a second list that includes non-essential qualities. Now

- Create a specific number of artworks that fulfill these allegedly essential qualities. Having defined a list of essential qualities, you now create work that tries to fulfill them. You can define upfront how many pieces you aim to create (eg. five, seven or twelve artworks), or you simply decide this along the way, as you keep finishing new works. Actually creating these works will be accompanied by your continuous judgment of whether your interrogation and analysis were “correct”. You will realize that your some things were less important than you thought, while others are ultimately more relevant than you thought.

On this path of creating work, it’s OK to have doubts. It’s OK for you to wonder whether what you’re doing is actually worth your time. These thoughts and feelings are part of your process of becoming an artist. How you deal with them is part of your personality – both as human and artist. Creating these works is the consequence of something uniquely personal, and thus vulnerable: your topics, your passions, your way of using tools, media and craft – your way of not just seeing, but now also adding to the world. - Judge the new works. You will come to a point where this interrogation-by-creation will feel finished. This enables you to judge the work (and the entire sequence of works), and compare them to the list of essential qualities defined beforehand. How do they compare? What did you learn?

Approaching the creation process like this results in having created something “complete”, something that tends to have strong degrees of self-explanatory power. We are often better able to understand, relate and judge a sequence of works, than single pieces – maybe because the contextual repetition aids our understanding. In addition though, a work sequence enables you to document and/or exhibit it. It can mark the first, or another, chapter in your artistic life.

Each of the works in the sequence will have unique aspects that aren’t shared by the other pieces. You can repeat the interrogation process for each of these works or ideas, resulting in your art not only being fed by your external passions, but also by the work you created thus far. It lets your work archive become a recursive platform of self-interrogation.

To understand what to do artistically, investigate your mind, and you will transcend stagnating on craft.