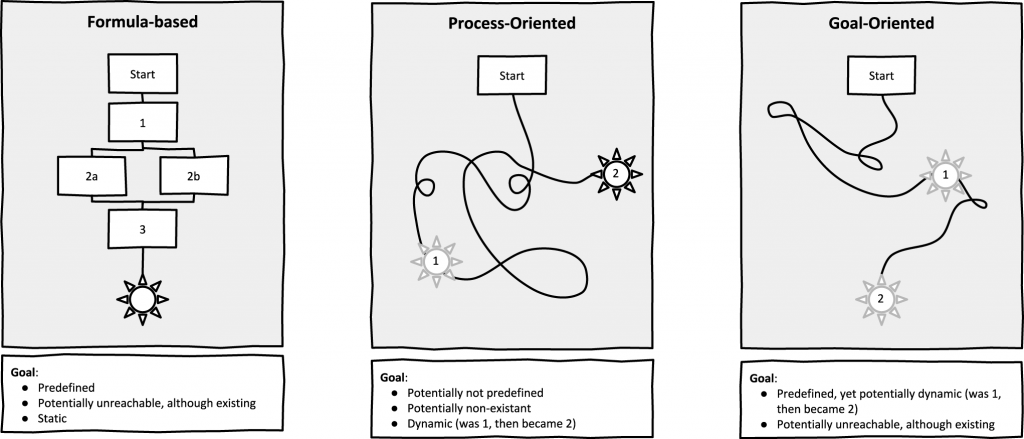

Since contemporary art is a platform for almost any personal expression, there cannot easily be general guidelines or expectations on what an artist should do: your art can be whatever you want it to be – which is both potential and burden, especially to beginners. What to do, and how, and why? Everyone needs to find their own answers to these questions, which is why students and emerging artists usually need years to understand their terrain: themselves, their output, and other people’s resonance. While some will love the inherent openness, the guideless exploration of artistic processes, others will feel overwhelmed by too many possibilities. Your artistic practice can feel like a sea, with you in the middle, and no land in sight. Murky. What direction to swim to? It’s these feelings that let us look for external support – through books, conversations, art school, etc. But can others help you find your way?

We understand the world by naming it; writing or talking about our experience allows us to analyze and interpret it. We might not have a solution, but we are beginning to tackle the problem. This helps us to develop ever more refined opinions about the world – whether in our personal lives or our art practice. The more we engage in discussions about our ideas, the more we get to listen to other people’s ideas in return. This enriches us, since we get to experience how others understand and name the world. In the best of cases, a mutual, respectful exchange of experiences is enriching to all participants. Yet a lot of people aren’t particularly respectful or sensitive. Interacting with them can become a burden, or have hidden costs; this creates new challenges: we want advice, and might actually receive it – but can we trust someone else to know what we actually need? And since it might have been ourselves that asked for help: can we even trust ourselves to know what we want, and whom to ask for support?

Most people want support when they start out: we don’t understand the standards and histories of our tools and media, and have few clues about anything. Yet the further we progress, the more we will usually want to deviate from standards: after all, art is ultimately about your individual expression – how well will general standards express them? Growing as an artist thus requires us to dissent; to deviate from advice and established norms. The terrain in which we operate is not originally defined by us; rather, it’s the end result of those preceding artists whose footsteps we follow (and expand). Understanding our terrain thus often requires us to dive deep into the work of other artists first – but we need to detach eventually. We need to pursue ourselves. The more we were looking for external advice and validation, the harder we might later have to establish ourselves as authority in our work. The more we let others tell us what to do (and what not to do), the more we let others define what’s good and bad, the harder we will later be challenged by our lack of authority. In the worst case, you create a situation where you strive for external validation of whoever you ask for advice – without following your own trail. In school situations this might feel to be valuable – but once you leave their hierarchy and safety, you’re lost once more, and in a harsher setting: instead of being a dependent student, you’d now be a graduate without authority over their work.

Consider the following when seeking external validation and advice for your work practice:

- Maintain creative authority: When you ask for advice or support, you need to be sensitive to (a) your urge to transfer authority to whomever you’re talking to (after all, someone else might know better, or, in the case of a teacher, might actually know “best”), and (b) their urge to demand or implement authority over your work. You might want to know why a drawing doesn’t feature the rhythm you were aiming for – is the ensuing conversation actually discussing this?

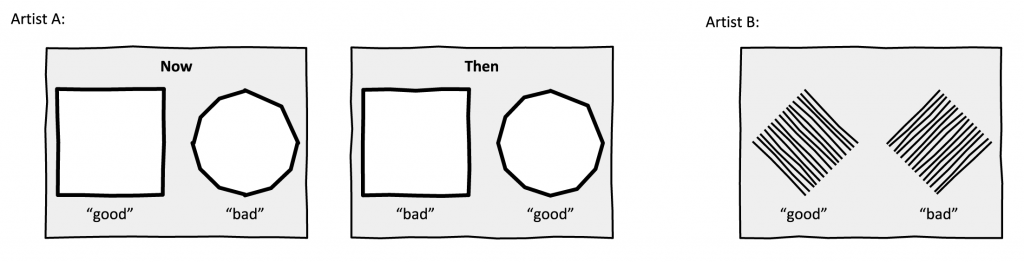

Understand that asking for advice should never entail transfer of work authority: you usually want to increase knowledge of standards (how to weld, how to clean a brush, how to sand stone, etc), to eventually be able to decide whether to use or deviate from them. The more complex the topic, the more challenging it can be to understand your own voice within the expectations of standards: understanding painting compositions, film editing or mastering a choreography thus are prone to external advice that might sound legitimate, but might also strongly intervene with your artistic vision. - Investigate your urge for advice: The more you feel lost, the more you might want support and validation, and might welcome strong opinions (“Do this! Don’t do that!”). This risks prematurely diminishing the ambiguities, and thus the potentials of art. Artists need to develop their tastes and preferences; the stronger these are refined, the more likely they might want to apply them even to other people’s work. Yet applying one’s tastes to someone else’s work, especially when asked for help, rarely is sensitive. Instead, it usually leads to misunderstandings and frustrations. That’s why the stronger someone tells you what’s right and wrong in your artistic processes, the more worried you should generally be. The more you should question their intention.

- Good advice tends to acknowledge you and your situation: Good teachers support their students in exploration according to your own capabilities. When someone criticizes you (positively or negatively), always ask yourself whether they know you, know who you are, and what you want to achieve. The less they’re interested in you, the less they are able to offer individualized feedback. If they euphemize this by mentioning the purity of art, take special care: there is nothing more pure than humans; an advisor discussing art to be of higher value than you, might be more fascist than is healthy. They might care about the topic (and themselves), but not about the subtleties of your work, or you.

The obvious exceptions are works of art that are racist, sexist, or otherwise intentionally evil: it’s human to not want to get into the details of them, but to simply disregard them and their surroundings. - Understand the dangers of discrimination (against specific tools, processes, semantics) in exploratory processes: Independent of their intention, people’s opinions and advice discriminate; they define what intentions, processes, semantics or tools are valuable, and which ones’ aren’t. This is exactly why people who feel lost, turn to others for advice: when we’re lost, we want to be shown the right path, and want the wrong path to be discriminated against. A guide (whether a person, or a book like this one) is wanted exactly for its discriminatory capacity: against dead-ends, energy vampires, outdated ideas etc. A guide is expected to discriminate against what’s bad. Yet in art, who can know what’s bad? More specifically, who can know what’s bad for you?

What you’d want most (strong opinions) is usually not what you should be given. In a murky sea of possibilities, you might think to want direction. But if that is offered, it shouldn’t be through strong opinions. It should be through advice that helps you find yourself, and your way forward: through encouragement and respect, and tools that enable introspection and self-assurance, and an increasingly personal mode of operation – both in creating and discussing your work. Advice and support should be aimed to increase your knowledge about the topic’s complexities, so that you can find your own tastes within them, and thus ultimately strengthen your own voice.

When in darkness, of course we look for light. In case of desperation on behalf of the artist, this situation has relevant pitfalls though: other people’s opinions might be seen (or posed) as canonic, as pure – where they obviously can’t be more (or less) than the result of that other person’s individual experiences, hopes and dreams. Other people are essential to our progress. We depend on their input to get to mastery (and beyond). But since the pure darkness of lacking knowledge also makes us vulnerable to negative influences, it’s important to understand that ultimately, no one can help you to find your voice. People can support your path, but it’s you who needs to want to pursue it. The peak of the mountain that is you, can only be climbed by you.

Imagine yourself as small, tiny light in utter darkness; while you might feel irrelevant, that small light is yours alone. It’s not nothing. It’s a beginning. In theory, you can modify it in any way, without having to rely on other people’s judgement: this moment of individuality is the soul of all art. We might fear to increase our brightness; after all, it might show us parts of ourselves that we aren’t really happy about. Some of us small lights would at times love to be within the safe boundaries of a stronger light: teachers, more successful artists, gatekeepers, friends. Yet if you continuously stay in someone else’s cone of light, it will be impossible to understand your own light, yourself: you can’t shine in situations made bright by others.