After having read the anatomy of art pricing, here are further general pricing facts:

- Prices need to reflect the economic situation of your initial target audience – not your production costs, research and production time, or how much you like or are satisfied with your work. Specifically, your work’s price needs to make sure that you have access to buyers who can afford it. That’s why a piece created by you, even though it might feel to be qualitatively “better”, can be priced lower than some other artist’s piece you deem “worse”, but is exhibited at a top gallery (consider reading this post about quality): if they have a sales network that enables them to sell the work, or the artist established a brand that allows for (or expects) this kind of work, then that’s a strong fact to consider. If you ignore this reality and price your work similarly, you risk not being able to sell it; and even if you sell it, it remains unclear whether you’ll be able to sell the next work at the corresponding price level.

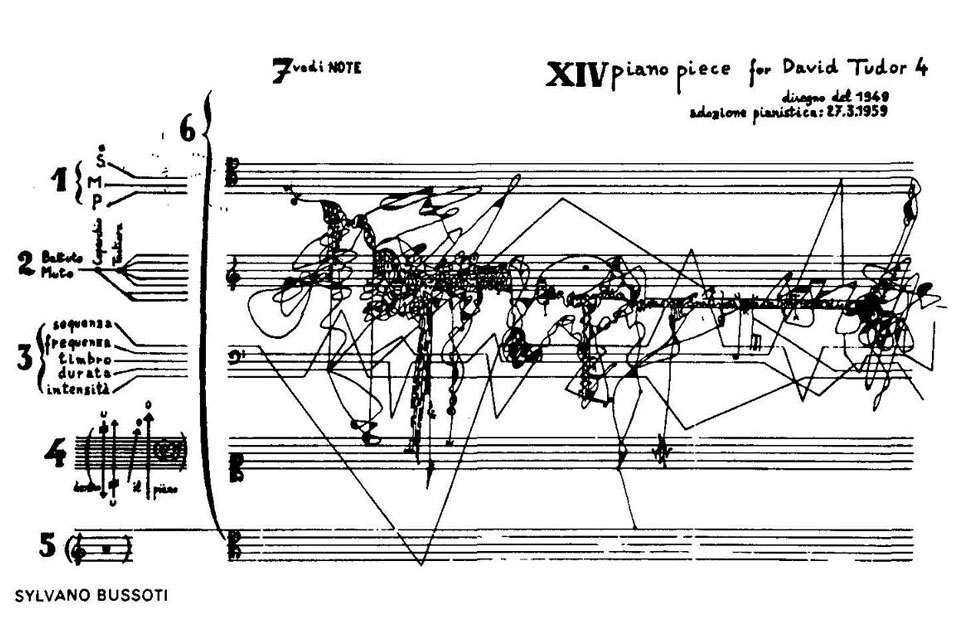

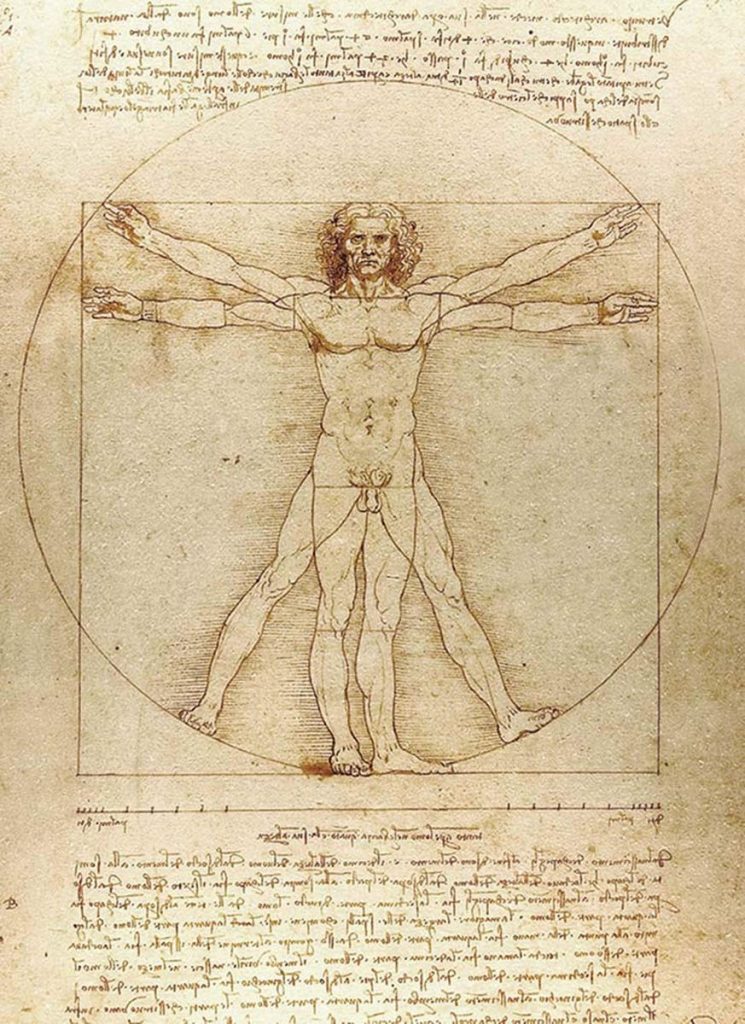

Outsiders to the art world (which includes younger, inexperienced artists) sometimes belittle the expensive works exhibited in galleries – especially if the work doesn’t pursue well-established craft ideals: “How can this cost so much? Anyone could do this!”. The reality is manifold: (a) not everyone could create this work – it’s usually a consequence of years of interrogation and manifestation; (b) not everyone could make a successful brand of it, and (c) not everyone would manage to establish proper sales channels to sell it. - Initial pricing requires knowledge about market access and target audience. Prices that feel too expensive to someone, will feel too cheap to someone else. This means that you can’t simply ask people to define prices for you – rather, you need to understand what target audience is within your reach, and what their financial capabilities are. If your parents are billionaires in the USA, your artwork’s initial price level will differ drastically to someone who creates the same works, but lives in the slums – simply because of the people you have access to. Don’t ignore your personal economic surroundings and market realities.

Collaborating with a gallery changes this, since they will have detailed knowledge about the financial range of their collectors. - Prices that are too high can make sales harder or impossible. Prices can be seen as statements, with negotiations challenging these statements. Overshooting price levels risks for negotiations to never happen, if buyers either don’t have enough money to even demand a discount, or do have enough money but don’t feel the price to be justified. If sales don’t happen at all, your price range is likely to be off. If they do happen (but not often), the situation gets more complex: you might sell more if your work would have a lower price tag – but this doesn’t guarantee that your annual earnings (which are a consequence of your sales quantity and your work’s price level) might be higher. Even if your sales are less frequent, you might generate the same (or more) money than with lower prices. Finding a proper balance will take time, and is challenging because the market doesn’t seem to enjoy pricing experiments. As long as you don’t have a strong market, this might not matter, but the further you progress, the less options you might have.

- Prices are often interpreted to signify quality – being too low can produce distrust in the work’s quality. Art is judged differently by everyone – there’s no single, monolithic quality standard to understand an artwork’s objective value. While art is subjective, money isn’t: it’s entirely established as signifier of something’s value. Contrasting the ambiguities of art with the clarity of monetary ascriptions clearly shows the latter having extreme authority over the former; it’s hard to disassociate these two. Consider an artist who is strongly established in one territory, but not internationally. If their work is exhibited abroad (where it’s unknown), people will still see the work’s price level – and derive quality ideas about it (“This is way too expensive!” or “This price shows how good the piece is”, etc).

Where prices ideally should reflect quality, the reality is that they reflect market penetration and brand visibility. Prices signify the quality and sales expectations of the seller’s network, and shouldn’t be used to infer an artwork’s artistic quality – but in actuality, people do exactly that, most of the time. The price of something is predominantly used as a measure of value, and thus of quality and integrity – especially by those without a strong inner compass about art. When an artist decides on a low pricing level, they’re implicitly sending out signals: “This is the work of a newbie”. If they’re too low, they’ll also signal that something is fishy, and potentially bad – or even fraudulent: “This work might be sloppy, the artist might not have a strong sales network, and might not care about pursuing their passion professionally”. This can be especially true for clients who don’t trust their own quality judgements: instead of seeing a bargain, they might fear to see failure.

Prices influence the perception of art to the point that a shooting star’s work might become less noteworthy than their artwork’s unexpected price range. Extremely high price levels can also lead people to distrust the work’s quality: can any work really be that good and important? The challenge lies in understanding your target audience’s economic expectations, and work from there. - Pricing is not the only external quality signifier: Your work’s price level influences your art’s perception, but isn’t its only external quality signifier; social media following or general fame might be others. Imagine an artist without gallery representation, yet with an extremely strong social media following. While their following might not be able to buy their work at its “normal” price level, the artist could bet on sales quantity, and opt to sell at a fraction of the price. This might be better for them than to sell through galleries (which rids them of 50% revenue), especially if they dislike certain aspects of the art world (elitism, dependency on galleries, etc).

An artist like this would have external quality signifiers pointing in extremely differing directions: following, yet no gallery. Amazing art, yet priced extremely competitively. The challenge lies in understanding what kind of market access feels right, and generates enough sales. This topic is complex already because potentially existing previous collectors might see this as price dumping that loses them their investments – but it’s a dynamic that’s bound to happen more frequently, as social media progresses.

This dynamic gets more complex, the more further external quality signifiers there are: - Pricing doesn’t have to reflect your living standards or whether you could afford your own work. Never forget that for all the idealism that got you into the arts, you’ll most likely be a producer of luxury commodities: you won’t have a lot of middle-class collectors with three-kid-families, since their focus often simply lies elsewhere (to save money for emergencies, student loans, cars, hobbies and vacations).

While human culture needs the arts to thrive (film, literature, music, theater, dance, etc), buying art always is a luxury transaction. That’s why even with the purest intentions, your work will always be a luxury commodity to its buyer. Understand that while you might not live in luxury, the works you create will most likely only be affordable by people who do. - Prices for artworks are always attached to the artist, although it might be the gallery that defines them: Some represented artists benefit from galleries to manage their network and sales. This can give the impression that the gallery should define the artwork’s price level – after all, pricing is part of the economic domain, and thus better suited to a gallery (which is expected to understand economics best). While pricing obviously brings artworks very close to economic realities, an artwork’s price nevertheless isn’t ultimately attached to the gallery. In a way, it isn’t even attached to the artwork itself, but to the artist who produced it: A gallery can close down, retire or change owners, resulting in the artist to be without representation. A gallery can decide to end collaborating with you, from which point onwards your access to their network will be extremely limited.

For all these reasons, do not ever let go of pricing decisions: they are yours to make. At the same time, don’t ignore advice either: enter a dialog with anyone who wants to advise you about pricing your artwork. This lets you increase your knowledge and influence the decision, while enabling you to offer feedback. It has the added benefit of highlighting your interest in business decisions – to yourself and the gallery. This lets pricing be part of your range of action, resulting in shared responsibilities between you and the gallery. This lets you grow.

Consider reading the anatomy of art pricing, how to price your artwork as a newbie, and the formula to calculate art prices.