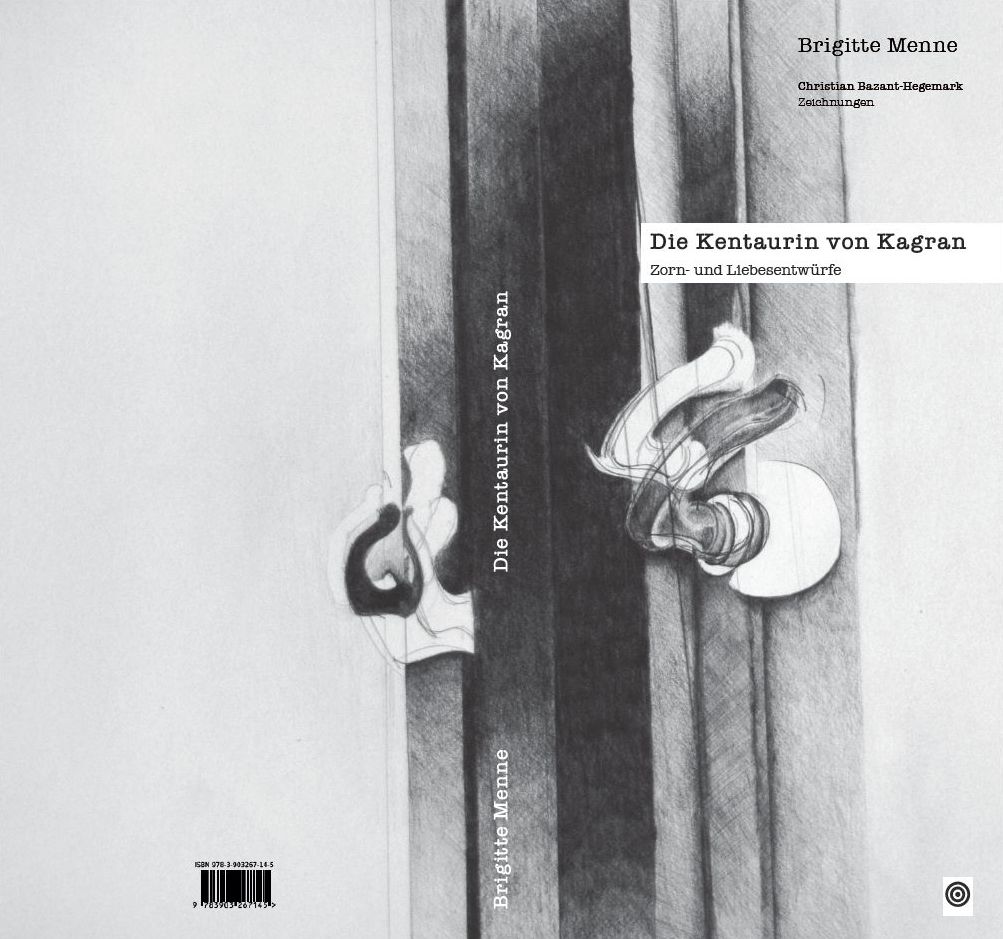

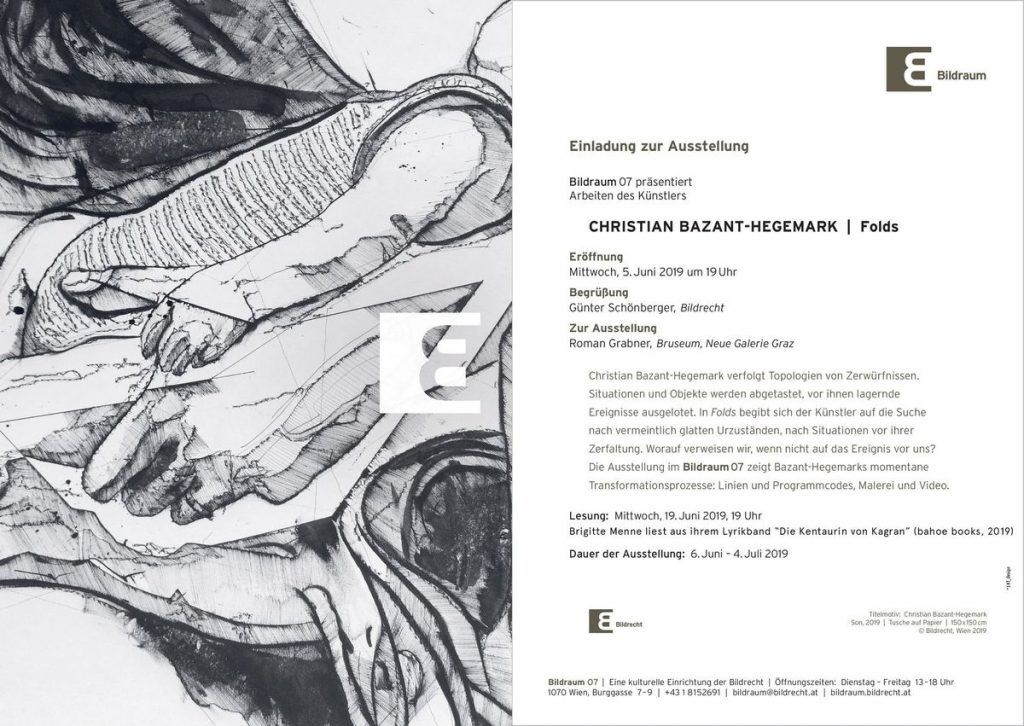

Jaqueline Scheiber wrote the following text for my 2021 exhibition “Trauma” at Museum Angerlehner. It was published in my book “Trauma”, alongside texts by Günther Oberhollenzer and Andrea Kopranovic.

Trauma, Jaqueline Scheiber, 2021

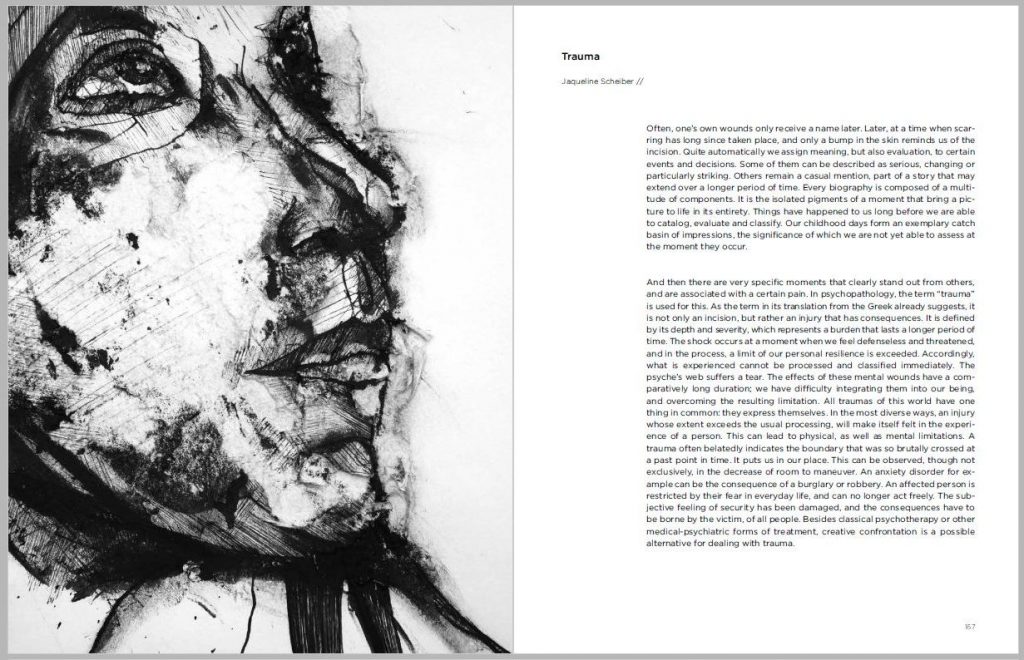

Often, one’s own wounds only receive a name later. Later, at a time when scarring has long since taken place, and only a bump in the skin reminds us of the incision. Quite automatically we assign meaning, but also evaluation, to certain events and decisions. Some of them can be described as serious, changing or particularly striking. Others remain a casual mention, part of a story that may extend over a longer period of time. Every biography is composed of a multitude of components. It is the isolated pigments of a moment that bring a picture to life in its entirety. Things have happened to us long before we are able to catalog, evaluate and classify. Our childhood days form an exemplary catch basin of impressions, the significance of which we are not yet able to assess at the moment they occur.

And then there are very specific moments that stand out clearly from others, and are associated with a certain pain. In psychopathology, the term “trauma” is used for this. As the term in its translation from the Greek already suggests, it is not only an incision, but rather an injury that has consequences. It is defined by its depth and severity, which represents a burden that lasts a longer period of time. The shock occurs at a moment when we feel defenseless and threatened, and in the process, a limit of our personal resilience is exceeded. Accordingly, what is experienced cannot be processed and classified immediately. The psyche’s web suffers a tear. The effects of these mental wounds have a comparatively long duration; we have difficulty integrating them into our being, and overcoming the resulting limitation. All traumas of this world have one thing in common: they express themselves. In the most diverse ways, an injury whose extent exceeds the usual processing, will make itself felt in the experience of a person. This can lead to physical, as well as mental limitations. A trauma often belatedly indicates the boundary that was so brutally crossed at a past point in time. It puts us in our place. This can be observed, though not exclusively, in the decrease of room to maneuver. An anxiety disorder for example can be the consequence of a burglary or robbery. An affected person is restricted by their fear in everyday life, and can no longer act freely. The subjective feeling of security has been damaged, and the consequences have to be borne by the victim, of all people. Besides classical psychotherapy or other medical-psychiatric forms of treatment, creative confrontation is a possible alternative for dealing with trauma.

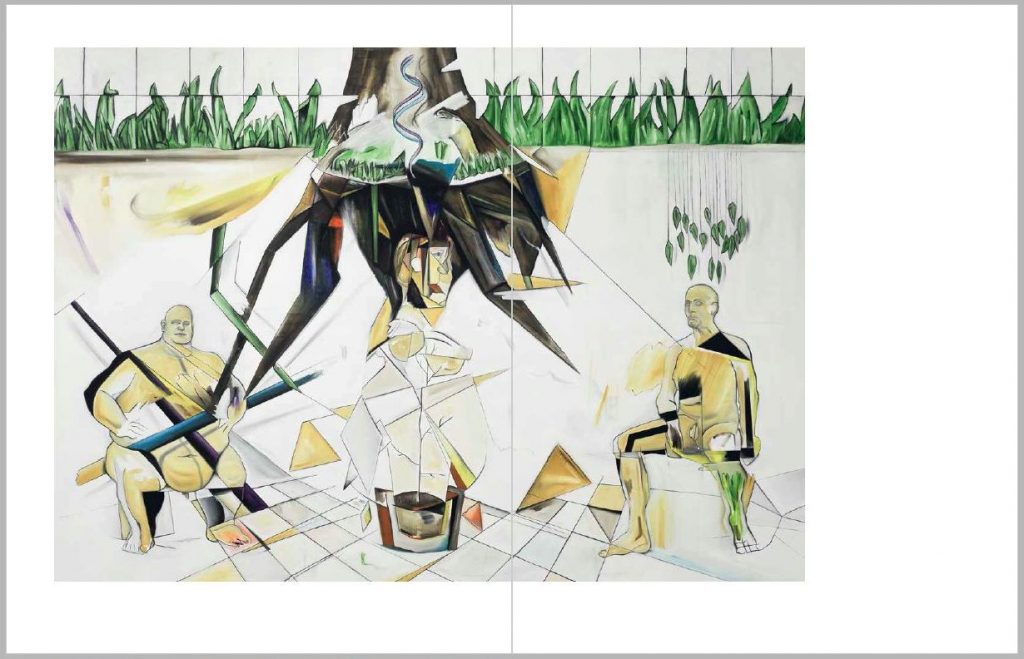

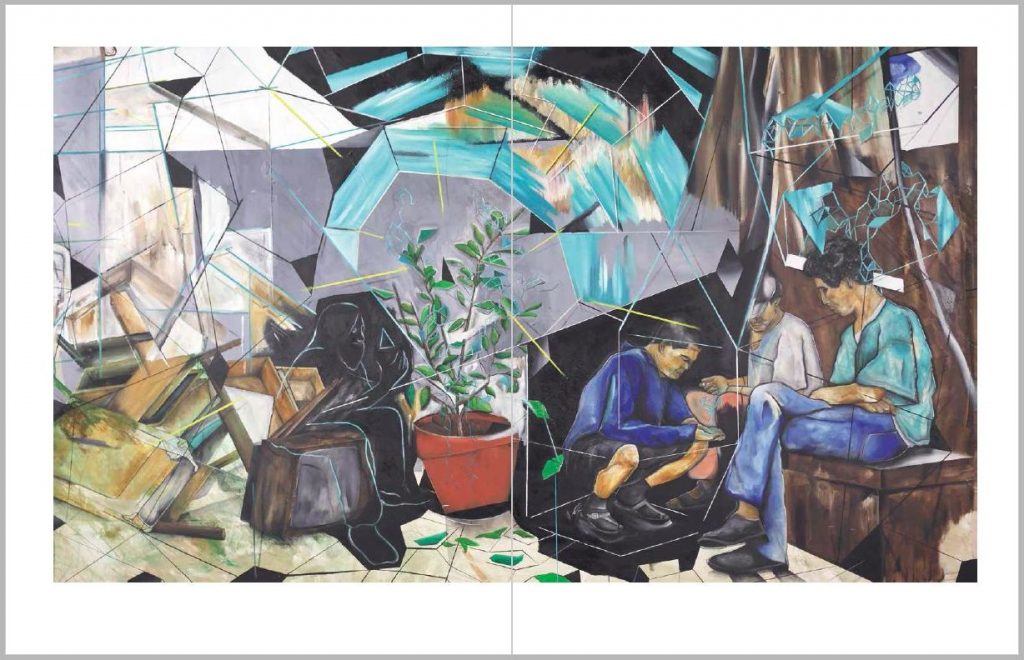

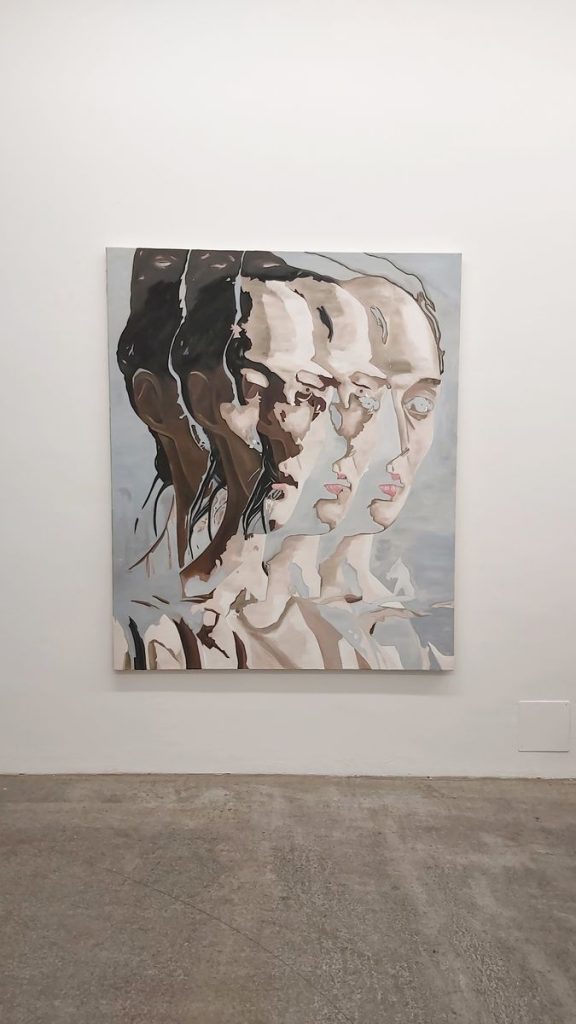

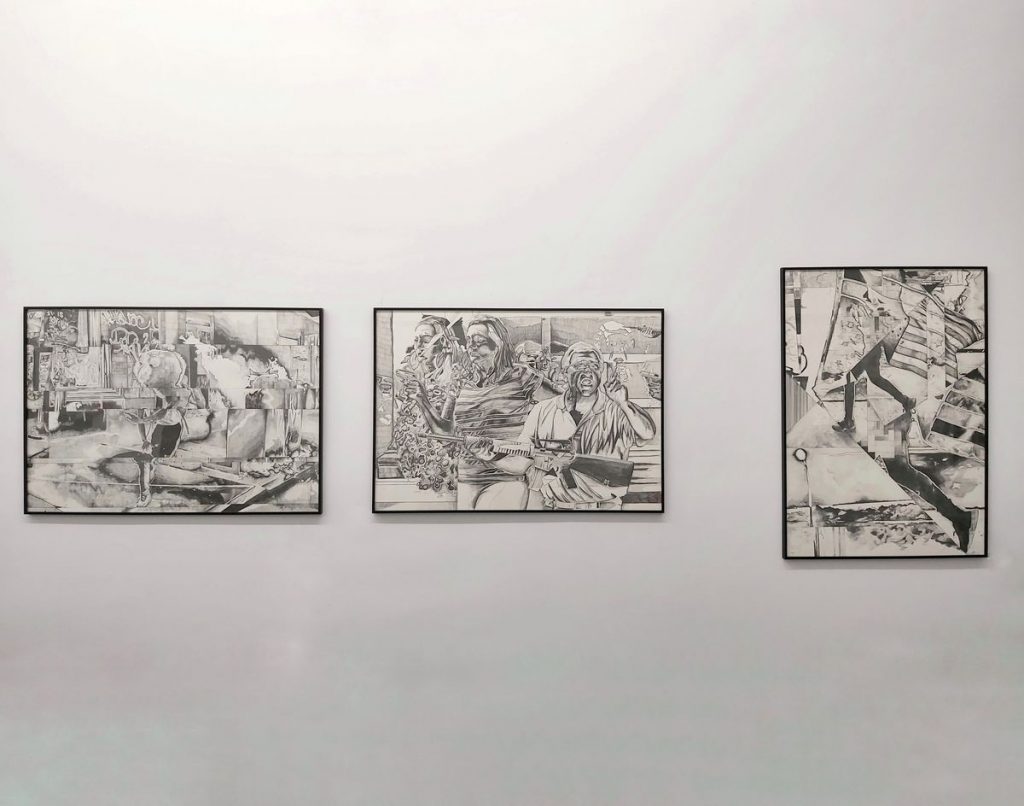

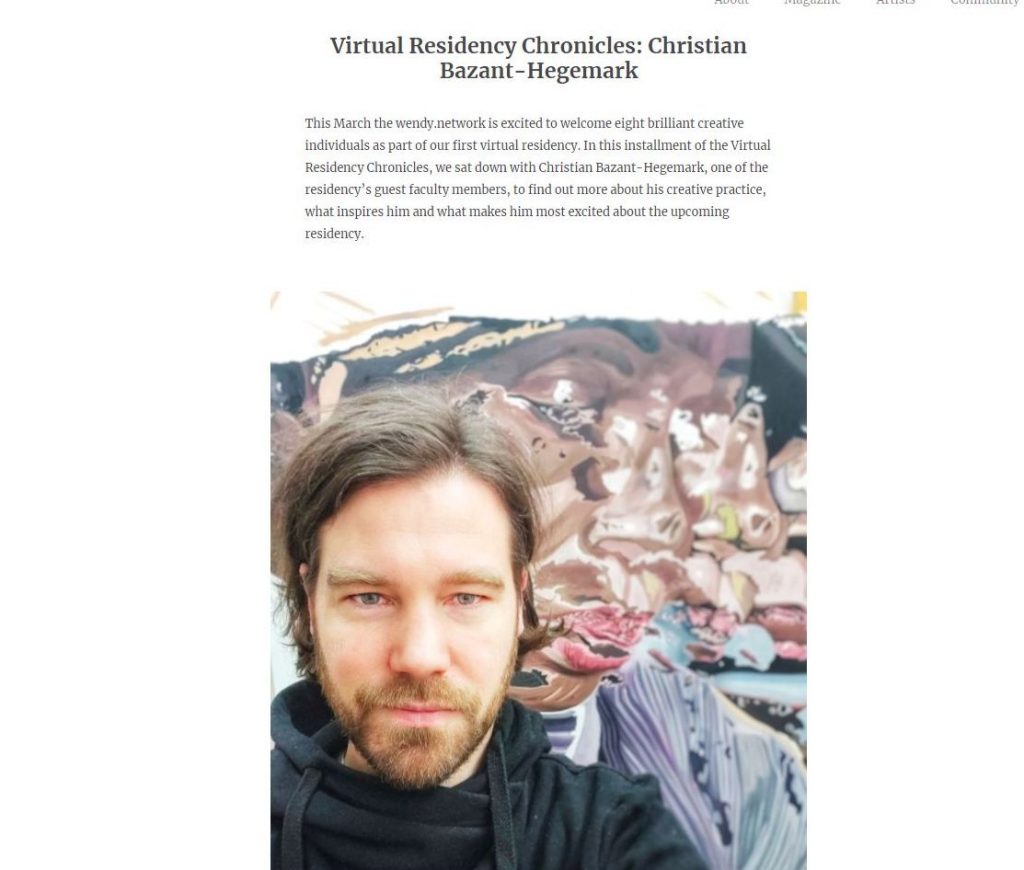

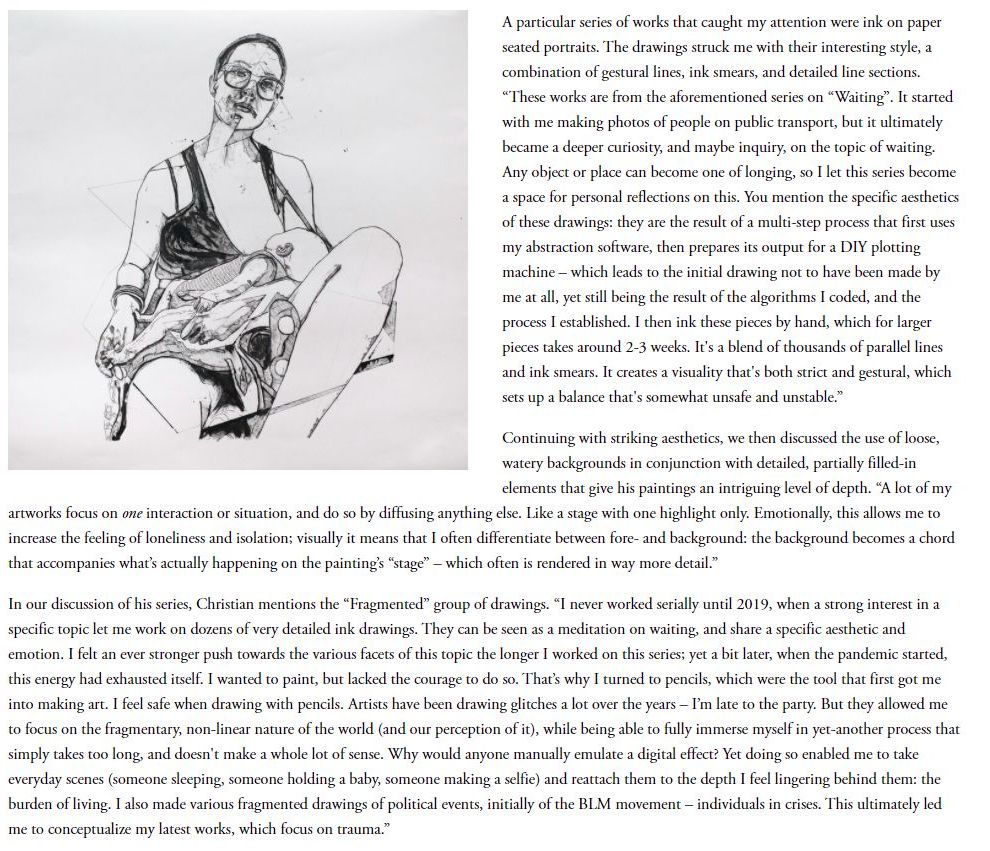

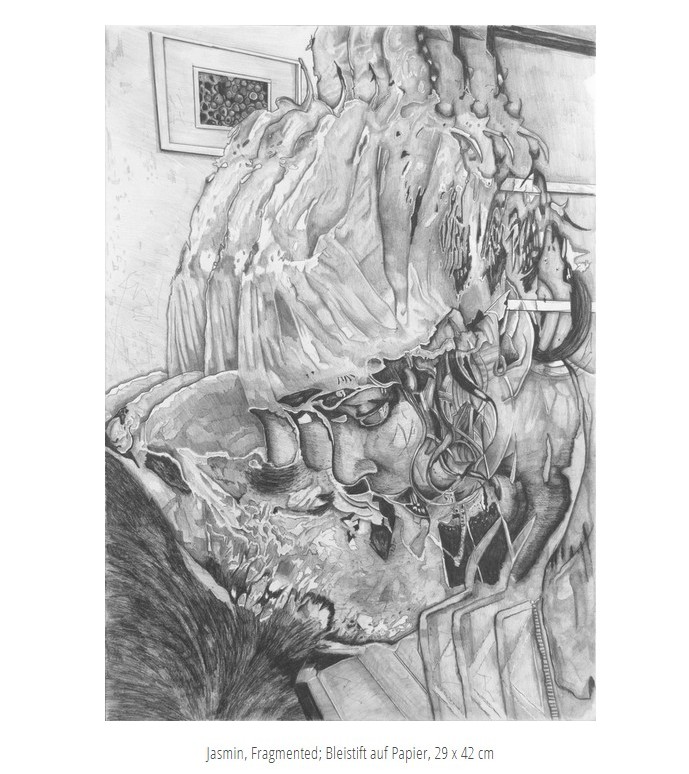

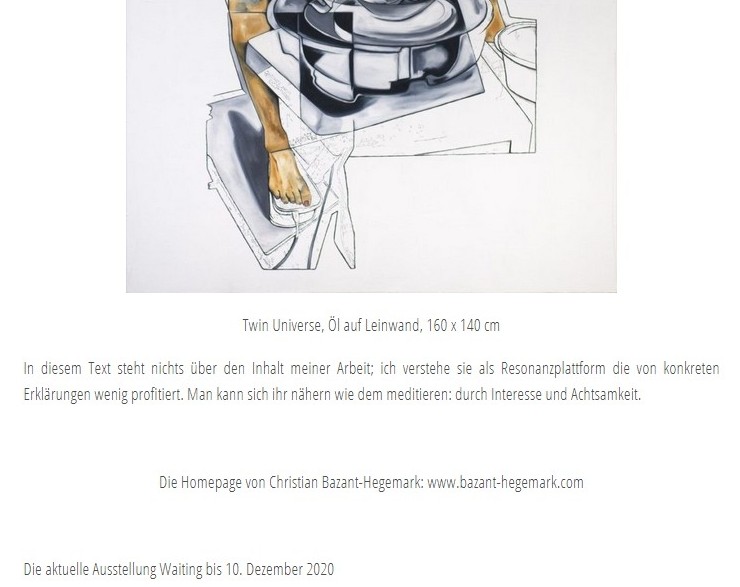

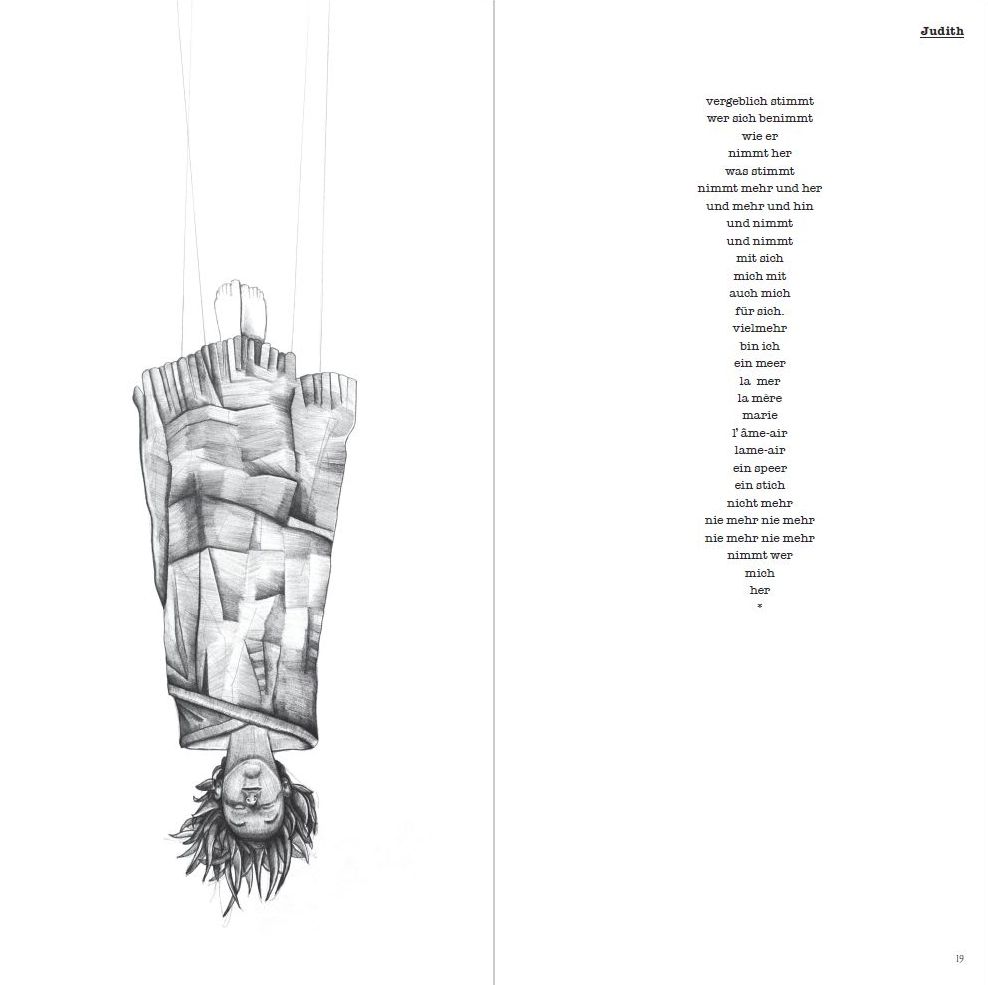

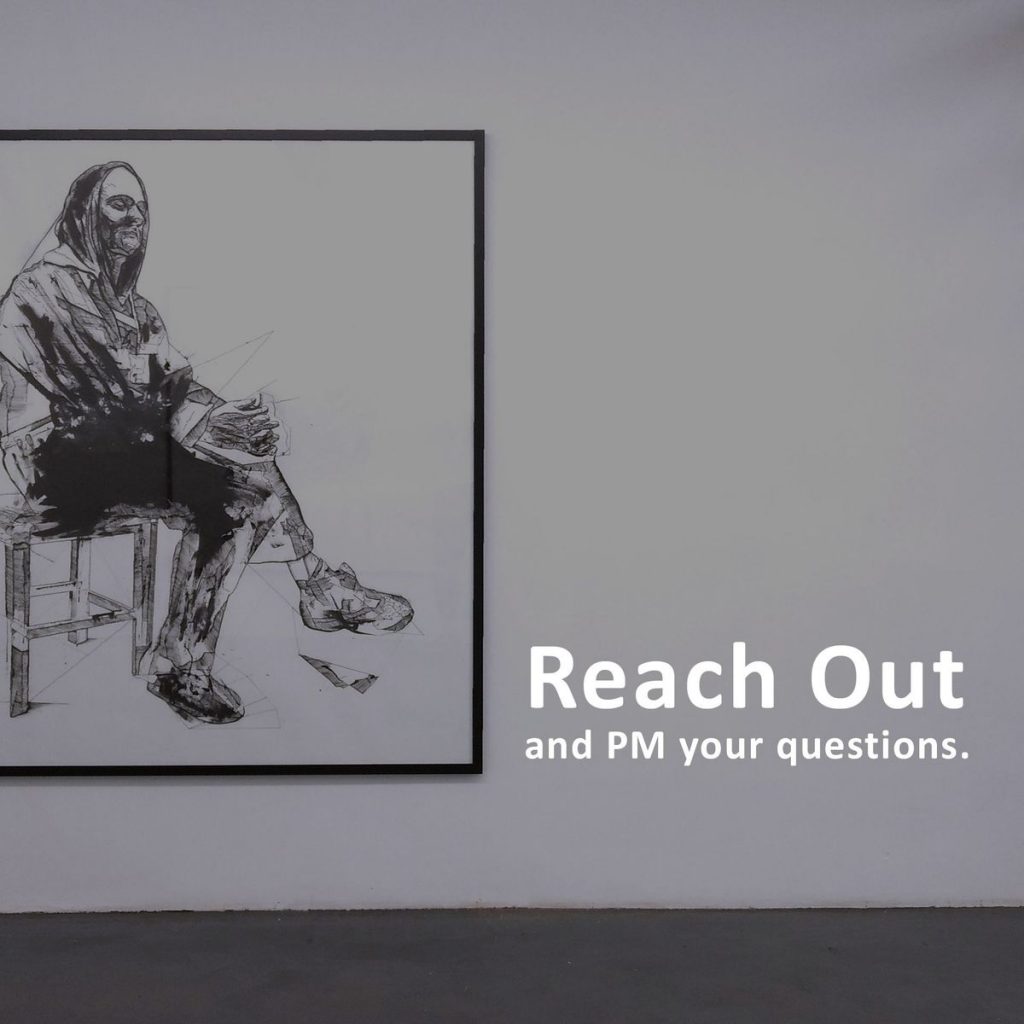

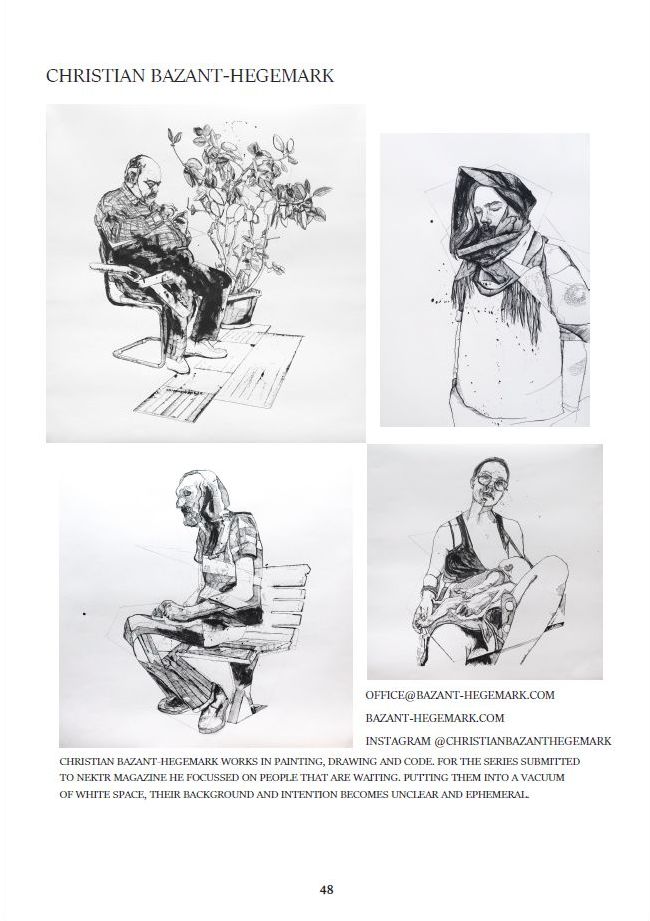

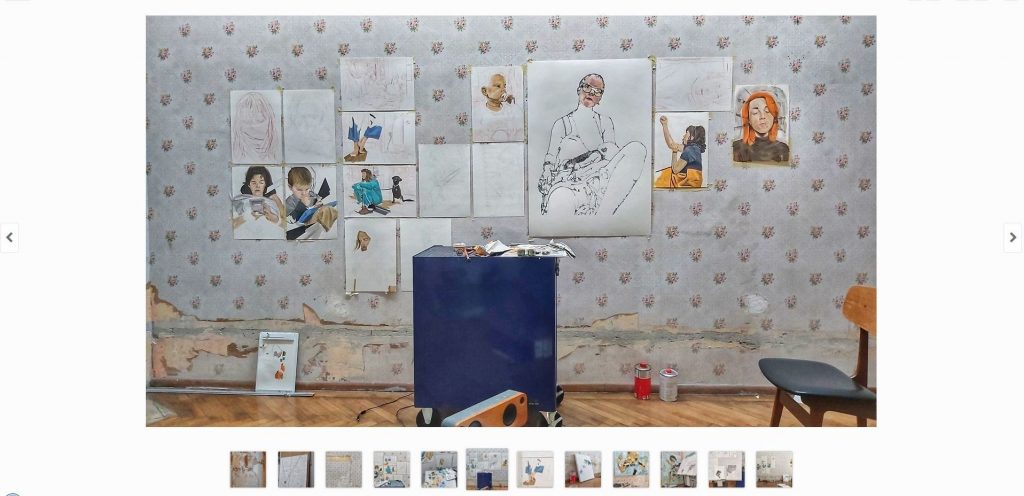

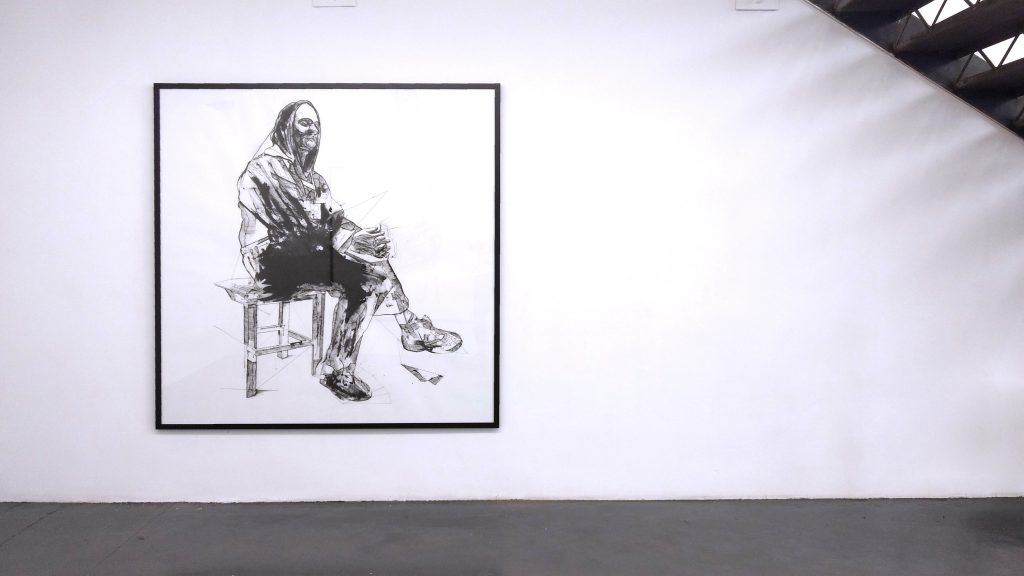

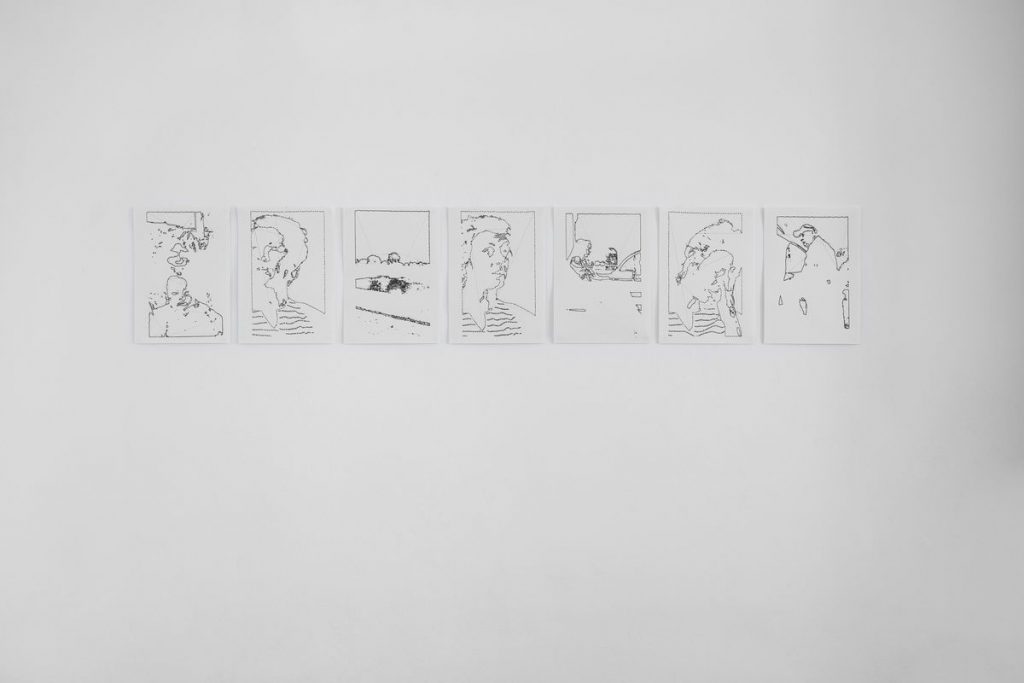

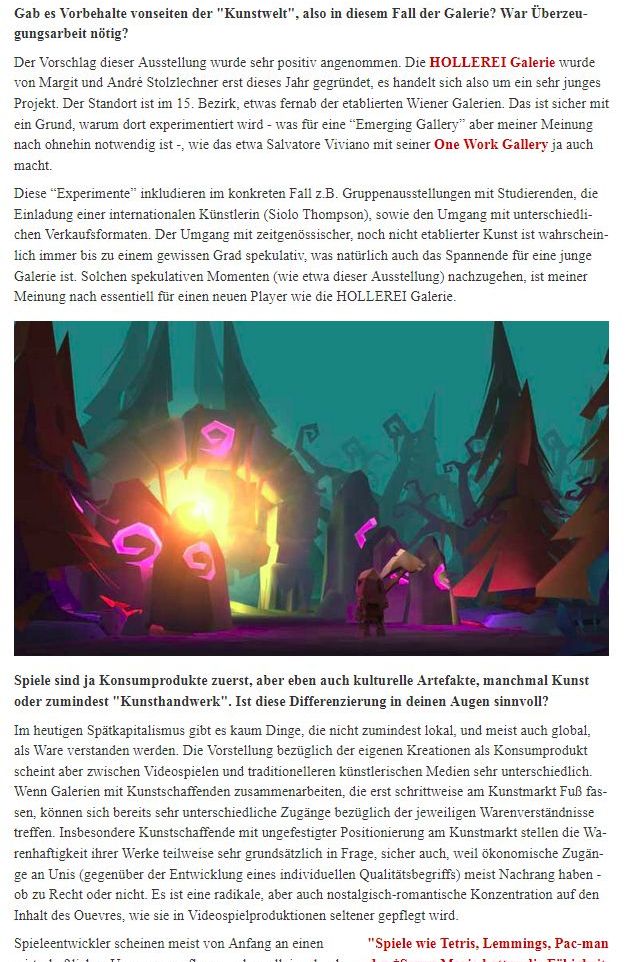

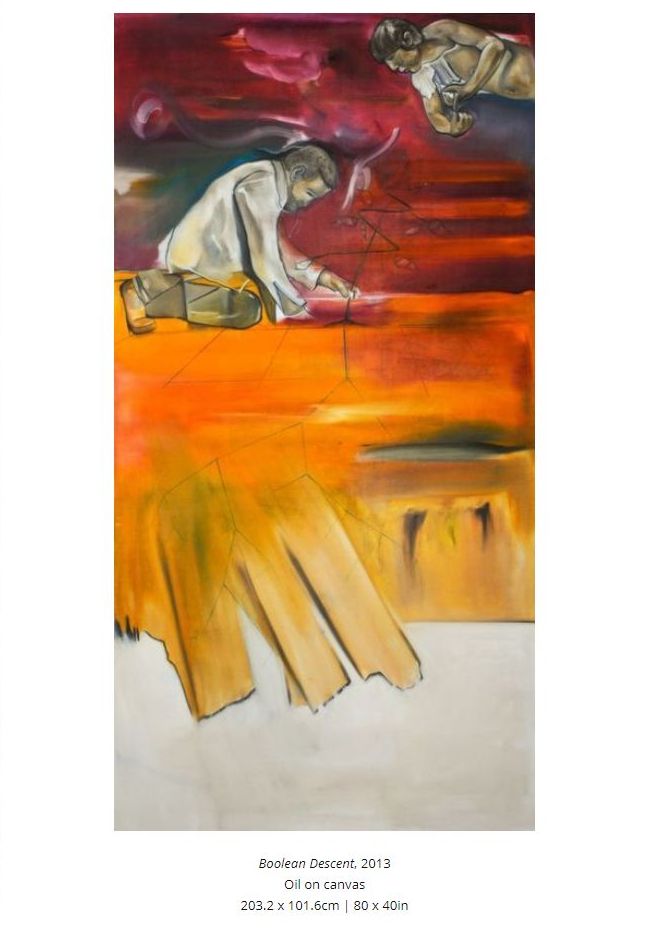

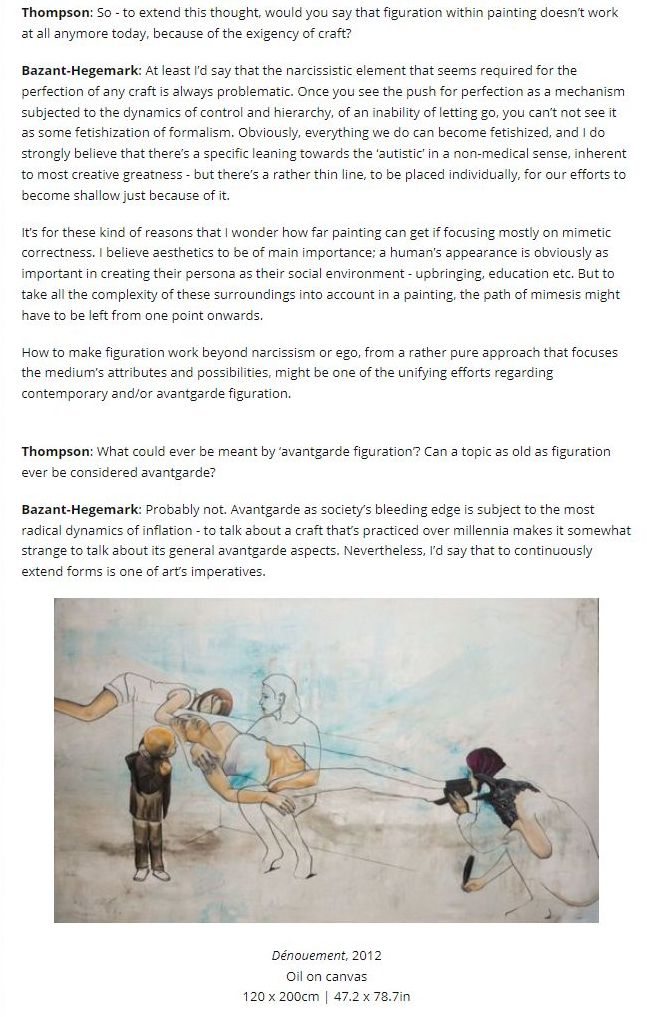

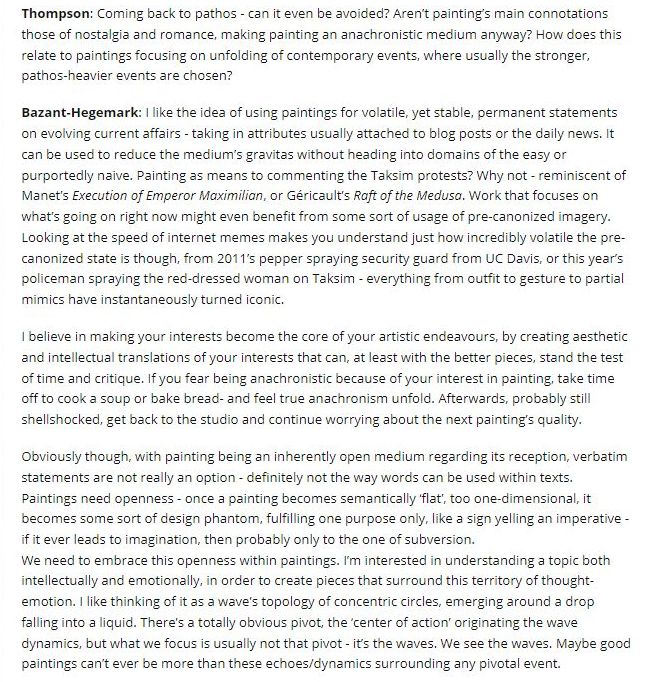

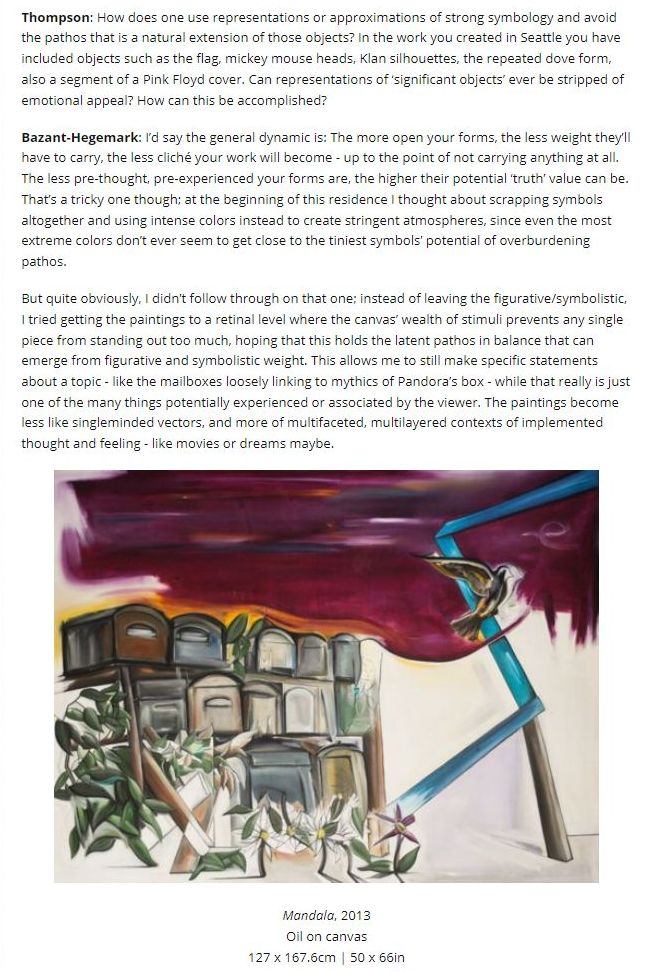

However, that isn’t what Christian Bazant-Hegemark did in the first place. While looking at the images, we do not have to go in search of the supposed incision, dissecting and analyzing the image details until we find clues to the severity of the artist’s identity. Rather, what can happen here is the creation of an atmosphere. Between the impact areas of the sometimes silent image moments, a variable opens that can unite our understanding of everydayness and trauma. The immediate encounter with works that at first sight do not satisfy any sensationalism, and in many cases do not use the usual visual language of pain, expands the idea that we associate with the rupture. Despite their spatial weight, the works often depict moments far removed from tragedy. It is as if the silence between the lines has been held under a magnifying glass. What becomes visible are not the bold headlines, the hand-wringing cries for help, or even forms of violence. On the contrary, at first glance the viewer learns very little about the direct connection to the traumatization.

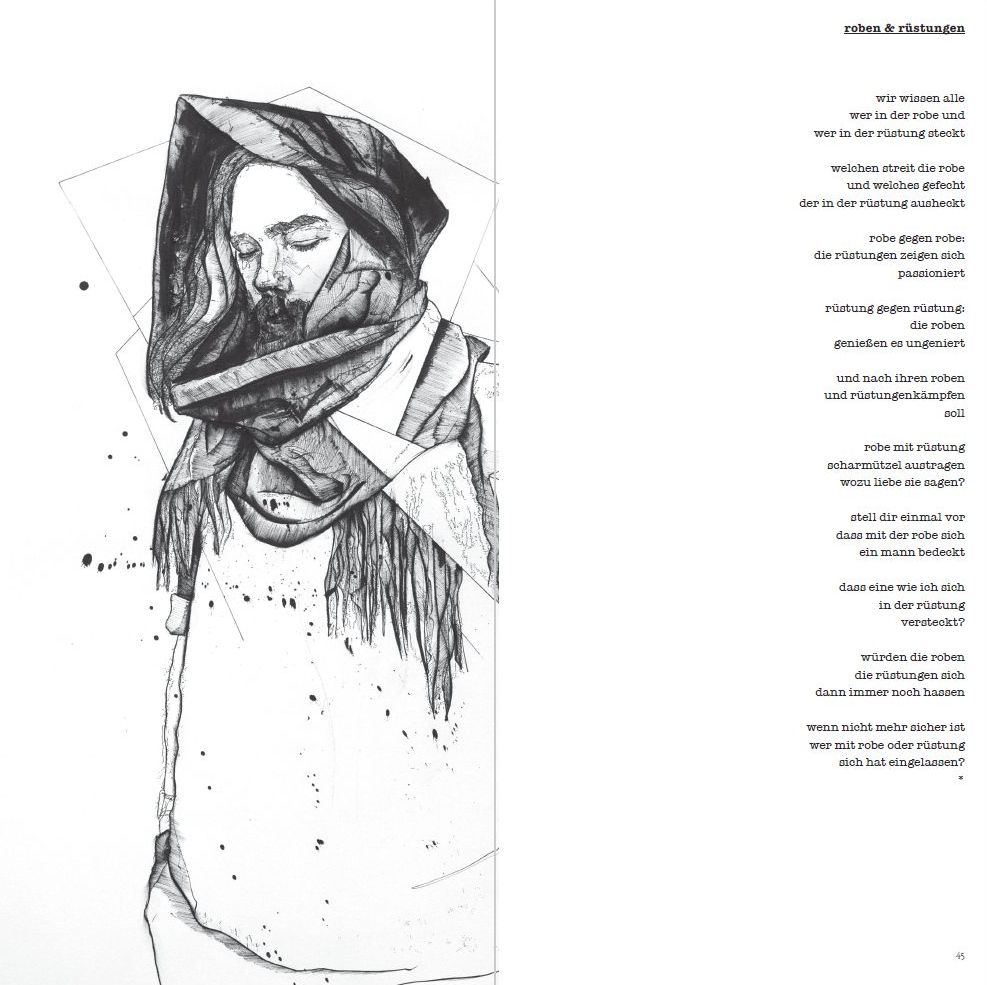

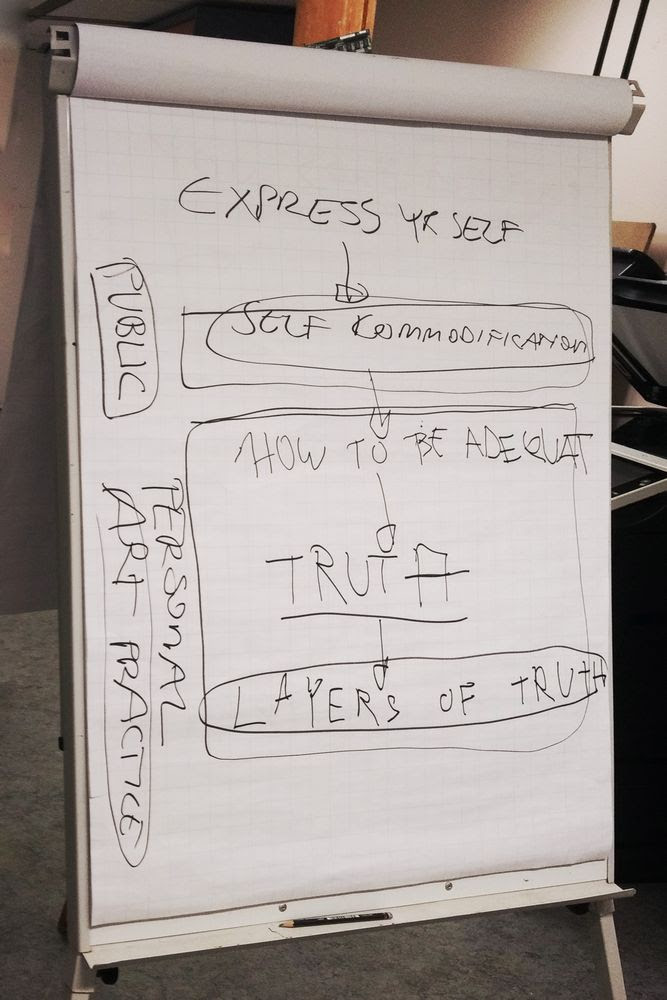

But before we finally turn our gaze to the core of this exhibition, the art itself, I would like to take one step back. The essential question we should confront is whether trauma, in order to exist, must be visible and palpable in external perception. In which spaces could those experiences so far unfold, and, further still – were allowed to unfold? Surprisingly, we find taboos for widespread phenomena of human existence. Concerns that affect broad masses are relegated to society’s background, and are treated with caution and secrecy. Grief, sadness, sorrow, mortification, loneliness and loss are not singular experiences of a few. They form a void, a hole whose encounter is inevitable. The only thing taboos achieve is the custom of having to experience such states of mind primarily alone. And exactly this propagation of an inherited secrecy fuels the purpose of letting traumas as such become visible in their scandal. Broken down, this means: what has always been with us and in us moves to the margins, and only again comes to center stage once we form a circle around it that causes a stir.

If one illuminates a human life in the sum of its milestones, one cannot avoid the fact that it is the acquired repertoire of feelings, of all things, that makes the sequence of scenes human. Feelings that also include, in different gradations and varying in intensity, negative and deeply wounded areas. So when we approach trauma, we equally approach the ordinary. Although the moment of injury is supposedly brutal, life with and around the shattering is one that follows its ways far from sensation. And it is at this point that Christian Bazant-Hegemark’s works converge with the theme of trauma.

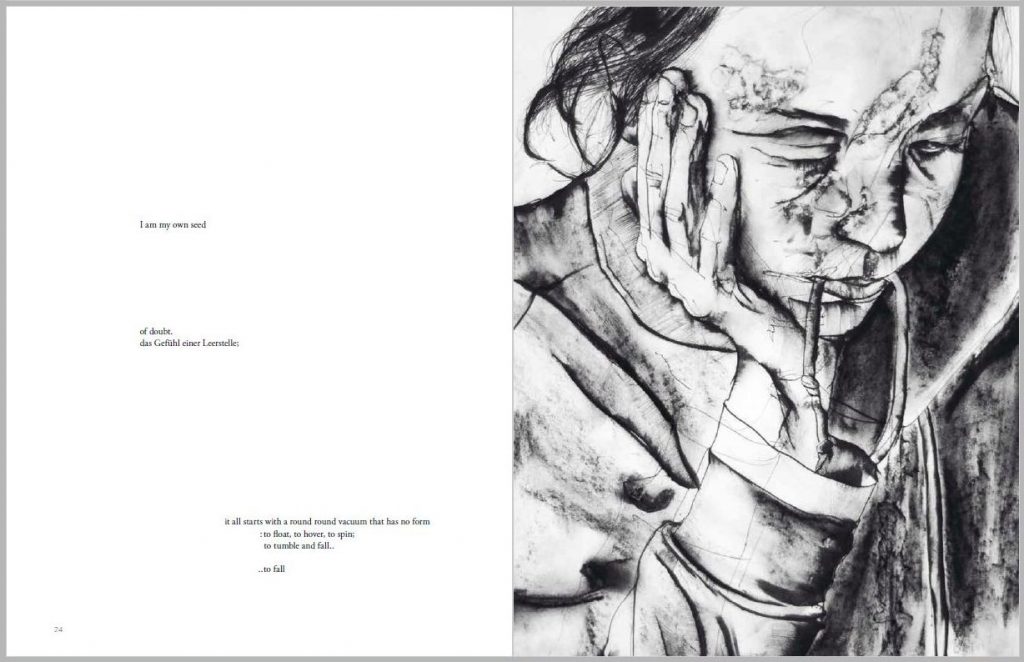

Not having to put the finger on the wound, turning away from the emerging curiosity and directing the gaze from the observation of the outside toward the inside. Approximating perspectives alongside parallels, reaching physical contact through movement and removing the silent space between the lines. Imitating directions, translating them from sketches on the palms of hands and brushing them off against the shoulder of the next person. Acknowledging resistance, exploring its boundaries and weaving it into a dialogue. Bidding farewell to expectations with the help of irritation, questioning one’s definitions, and perhaps adding some contrast to the inventory. Recognizing the familiar and encountering the unfamiliar. Discarding comparisons while realities grow up as equals and find their place in the hall. Drawing meaning from the spaces in between, demarcating the idle state and naming it. Seeing, not just watching, leaning without bending, and effortlessly sinking into depths. Leaving without remaining burdened. Meeting without becoming an opponent. Understanding, where there is no final word.

These are possible choreographies for approaching a concept that at first sight misses the description of the works. Works that, on second, third or fourth viewing, do not produce clues, but spheres that allow the examination of the spaces between, around and in the central topic. After all, aren’t those moments when we lose focus, precisely those that broaden our perspective, and create the horizon for possibilities?

Often, it is said, one only gives the child a name in retrospect. Thus one encounters the consequences of a wound with new tools, insight or skill. Inevitably, however, they are linked to our very personal and deeply intimate experience of life. They have shaped bodies that are different from one another, bodies that uniquely combine their marks and scars into an answer. If we ask about trauma, we are ultimately asking about life in its banality and simultaneous perplexity, about the spectrum of all possible narrative strands – we are asking about the nature of a soul that plays a role in all the stories and images. And through this, the trauma experiences space, colors and frames.

Trauma, von Jaqueline Scheiber

Oftmals bekommen die eigenen Wunden erst später einen Namen. Später, zu einem Zeitpunkt, wo schon längst eine Vernarbung stattfand und nur noch eine Hautunebenheit an den Einschnitt erinnert. Ganz automatisch ordnen wir gewissen Ereignissen und Entscheidungen Bedeutung, aber auch Wertung bei. Manches davon lässt sich als schwerwiegend, verändernd oder besonders markant benennen. Anderes bleibt eine beiläufige Erwähnung, ein Teilbereich einer Geschichte, die sich möglicherweise über einen längeren Zeitraum erstreckt. Jede Biografie setzt sich aus einer Vielzahl an Bestandteilen zusammen. Es sind die vereinzelten Pigmente eines Moments, die ein Bild in ihrer Gesamtheit zum Leben werden lassen. Lange bevor wir in der Lage dazu sind zu katalogisieren, zu bewerten und einzuordnen, sind uns Dinge widerfahren. Beispielhaft dafür sind die Kindheitstage, die ein Auffangbecken an Eindrücken bilden, deren Bedeutung wir im Augenblick des Geschehens noch nicht abschätzen können.

Und dann gibt es ganz bestimmte Augenblicke, die sich klar und auch mit einem gewissen Schmerz verbunden von anderen abheben. In der Psychopathologie findet man dafür den Begriff „Trauma“. Wie schon der Begriff in seiner Übersetzung aus dem Griechischen vermuten lässt, handelt es sich nicht nur um einen Einschnitt, sondern vielmehr um eine Verletzung, die Folgen aufweist. Sie definiert sich durch die Tiefe und die Schwere, die zumindest über einen längeren Zeitraum eine Belastung darstellt. Die Erschütterung entsteht in einem Moment, in dem wir uns schutzlos und bedroht fühlen und dabei eine Grenze unserer persönlichen Resilienz (Widerstandsfähigkeit) überschritten wird. Erlebtes kann demnach nicht sofort verarbeitet und eingeordnet werden. Das Netz der Psyche erleidet einen Riss. In der Rückschau haben jene seelischen Blessuren eine vergleichsweise lange Wirkungsdauer; wir haben Mühe, sie in unser Sein zu integrieren und die daraus entstandene Einschränkung zu überwinden. Alle Traumata dieser Welt haben eines gemeinsam: Sie äußern sich. Auf den unterschiedlichsten Wegen wird sich eine Verletzung, dessen Ausmaß die übliche Verarbeitung übersteigt, im Erleben eines Menschen bemerkbar machen. Das kann zu körperlichen, als auch seelischen Einschränkungen führen. Ein Trauma deutet oft verspätet jene Grenze auf, die zu einem vergangenen Zeitpunkt so brachial überschritten wurde. Es weist uns in die Schranken. Dies lässt sich nicht nur, aber auch in dem Rückgang von Handlungsspielräumen beobachten. So kann beispielsweise eine Angststörung eine Folge eines Einbruchs oder Überfalls sein. Eine betroffene Person wird von ihrer Angst im Alltag eingeschränkt und kann nicht mehr frei handeln. Das subjektive Sicherheitsgefühl wurde beschädigt und die Folgen davon muss ausgerechnet das Opfer tragen. Neben einer klassischen Psychotherapie oder anderen medizinisch-psychiatrischen Behandlungsformen, ist die kreative Auseinandersetzung eine mögliche Alternative der Bearbeitung von Traumata.

Allerdings ist es nicht das, was Christian Bazant-Hegemark in erster Linie getan hat. Wir müssen uns bei der Betrachtung der Bilder nicht auf die Suche nach der vermeintlichen Verletzung begeben, die Bildausschnitte sezieren und analysieren, bis wir Hinweise auf die Schwere der Identität des Künstlers finden. Vielmehr ist das, was hier passieren kann, eine Atmosphäre, die entsteht. Zwischen den Wirkungsräumen der mitunter stillen Bildmomente öffnet sich eine Variable, die das Verständnis von Alltäglichkeit und Trauma vereint. Die unmittelbare Begegnung mit Arbeiten, die auf den ersten Blick keinerlei Sensationslust stillen und sich in vielen Fällen auch nicht der üblichen Bildsprache des Schmerzes bedienen, weitet die Vorstellung aus, die wir mit dem Bruch assoziieren. Die Werke bilden trotz ihrer räumlichen Wucht oftmals Momente fernab von Tragik ab. Es ist, als hätte man die Stille zwischen den Zeilen unter eine Lupe gehalten. Was dabei sichtbar wird, sind nicht die fett gedruckten Überschriften, die händeringenden Hilferufe oder gar Formen der Gewalt. Im Gegenteil erfährt man als Betrachter*in auf den ersten Blick herzlich wenig über den direkten Zusammenhang mit der Traumatisierung.

Bevor wir unseren Blick jedoch endgültig auf das Kernstück dieser Ausstellung richten, die Kunst an sich, möchte ich noch einen Schritt davor ansetzen. Denn die wesentliche Frage, mit der wir uns konfrontieren sollten, ist, ob Trauma in der Außenwahrnehmung sichtbar und spürbar sein muss, um zu existieren. In welchen Räumen konnten sich jene Erlebnisse bisher entfalten und ferner noch – durften sich entfalten? Erstaunlicherweise finden wir für weitverbreitete Phänomene der menschlichen Existenz tabuisierte Räume vor. Anliegen, die breite Massen betreffen, werden im gesellschaftlichen Gesamtgeschehen in den Hintergrund gerückt und mit Vorsicht und Verschwiegenheit behandelt. Trauer, Traurigkeit, Kummer, Kränkung, Einsamkeit und Verlust sind keine singulären Erfahrungen weniger Betroffener. Sie bilden einen Hohlraum, dessen Begegnung unumgänglich ist. Tabuisierend daran ist lediglich der Brauch, genannte Gemütszustände vorrangig alleine erleben zu müssen. Und eben diese Weitergabe einer vererbten Verschwiegenheit befeuert den Zweck, Traumata als solches in seinem Skandal sichtbar werden zu lassen. Heruntergebrochen bedeutet das: Was immer schon mit uns und in uns weilt, rückt an den Rand und bekommt erst wieder eine Bühne, sobald wir einen Kreis darum bilden, der Aufsehen erregt.

Beleuchtet man ein menschliches Leben in seiner Summe an Meilensteinen, kommt man nicht um die Tatsache, dass es ausgerechnet das erworbene Repertoire an Gefühlen ist, das die Abfolge von Szenen erst menschlich macht. Gefühle, zu denen auch in unterschiedlichen Abstufungen und variierend in der Intensität, negative und zutiefst verwundete Bereiche zählen. Wenn wir uns also dem Trauma nähern, nähern wir uns gleichermaßen dem Gewöhnlichen. Obwohl der Moment der Verletzung vermeintlich brutal erfolgt, ist das Leben mit der und um die Erschütterung eines, das fernab von Sensation seinen Wegen folgt. Und an diesem Punkt konvergieren die Arbeiten von Christian Bazant-Hegemark mit dem Thema Trauma.

Den Finger nicht auf die Wunde legen müssen, sich von der aufkommenden Schaulust abwenden und den Blick aus der Betrachtung des Außen an das Innere richten. Sicht entlang von Parallelen herantasten, über Bewegung Berührung schaffen und der Stille die Zwischenzeilen nehmen. Richtungen imitieren, sie aus Zeichnungen in die Handflächen übersetzen und an der Schulter des Nächsten abstreifen. Den Widerstand anerkennen, ausloten und in den Dialog einflechten. Erwartungen mit Hilfe von Irritationen verabschieden, Fragen an die eigenen Definitionen richten und vielleicht einen Kontrast in den Bestand aufnehmen. Bekanntes erkennen und Fremdem begegnen. Vergleiche ablegen, während Realitäten nebeneinander ebenbürtig heranwachsen und in einem Saal so stehen bleiben. Aus den Zwischenräumen Bedeutung schöpfen, den Leerlauf abgrenzen und zu einem Namen formulieren. Hinsehen, nicht nur ansehen, sich lehnen, ohne zu beugen und ohne Überwindung in die Tiefe sinken. Verlassen, ohne belastet zu bleiben. Begegnen, ohne Gegner*in zu werden. Verstehen, wo es kein letztes Wort gibt.

Das sind mögliche Choreographien für die Näherung an einen Begriff, der auf den ersten Blick die Beschreibung der Werke verfehlt. Werke, die bei zweiter, dritter oder sogar vierter Betrachtung zwar keine Hinweise bieten, aber Sphären erzeugen, die die Auseinandersetzung mit den Zwischenräumen des zentralen Themas ermöglichen. Denn sind es nicht genau jene Momente, in denen wir Fokus verlieren, die unsere Perspektive weiten und den Horizont für Möglichkeiten schaffen?

Oftmals, so heißt es, gibt man dem Kind erst im Rückblick einen Namen. So begegnet man den Folgen einer Wunde mit neuen Werkzeugen, Erkenntnissen oder Geschicklichkeit. Unweigerlich jedoch sind sie mit unserer ganz persönlichen und zutiefst intimen Erfahrung des Lebens verbunden. Sie haben Körper geformt, die sich voneinander unterscheiden, Körper, die ihre Male und Narben einzigartig zu einer Antwort zusammenführen. Fragen wir nach dem Trauma, dann fragen wir letztendlich nach dem Leben in seiner Banalität und simultan herrschenden Verblüffung, nach dem Spektrum aller möglichen Erzählstränge – wir fragen nach der Beschaffenheit einer Seele, die in all den Geschichten und Bildern eine Rolle spielt. Und dadurch erfährt das Trauma Raum, Farben und Rahmen.